A War of Cartoons

Revisiting the little-known clash between Dr. Seuss and Charles Lindbergh in the lead-up to America's entry into WWII.

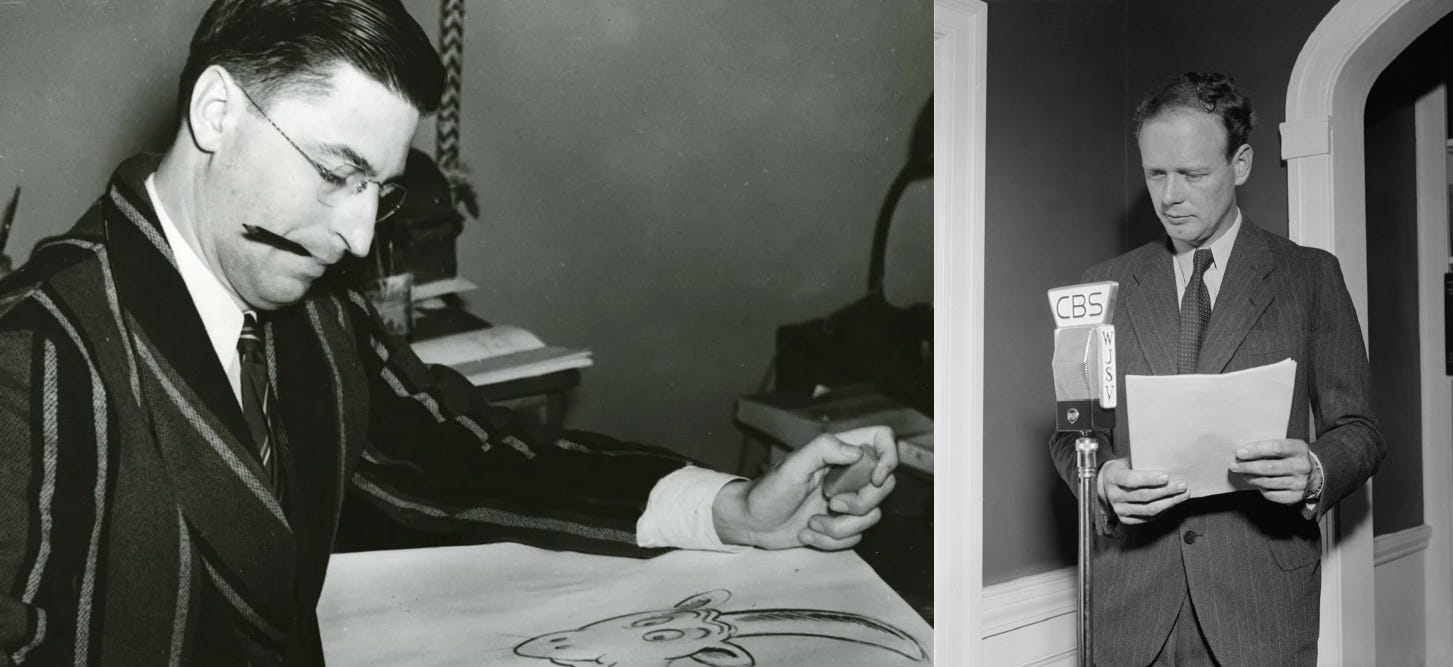

Theodor Seuss Geisel—better known by his pen name, Dr. Seuss—is the name most synonymous with a Dartmouth education: a legendary illustrator, cartoonist, children’s author, and namesake of the medical school.

Beating second-place contenders like Daniel Webster—or, more realistically these days, Mindy Kaling—Dr. Seuss remains the college’s most famous alumnus and one of the top ten best-selling authors of all time.

In honor of the 84th anniversary of Pearl Harbor—and our nation’s subsequent entry into World War II—we revisit a little-known battle waged by Dartmouth’s most beloved alumnus against an unlikely opponent: a polarizing national hero who also holds an honorary Dartmouth degree—Charles Lindbergh.

Geisel

Dr. Seuss had a lengthy and fruitful career—spanning eight decades—and, unsurprisingly, found his greatest success in his later years as a children’s author. While this chapter of Geisel’s life receives the most focus and celebration, his start as an advertising illustrator in the 1920s and his stint as a full-time political cartoonist in the early ‘40s are equally—if not more—fascinating.

After war broke out in Europe in 1939 and Nazi Germany saw major victories across the continent, Geisel became interested in expressing his views—chiefly, a passionate opposition to fascism abroad and isolationism at home.

He viewed the spread of war from Europe and Asia to the Western Hemisphere as inevitable—and considered isolationism a dangerous foreign policy that undermined American ideals—freedom from tyranny, specifically fascism.

Geisel began working for PM, a staunchly liberal, FDR-aligned New York newspaper, in 1941 as a political cartoonist, largely putting the creation of his burgeoning children’s book empire on hold. He created over 400 editorial cartoons for PM in a two-year span—at some points, as many as five per week.1

Some of these political cartoons have resurfaced in recent years and sparked controversy, directly leading his estate to discontinue six Dr. Seuss books in 2021 due to concerns over racist imagery. Yet it goes further—these revelations have implications for Geisel’s legacy, potentially complicating public perception of his lifework and his World War II–era political ideology.

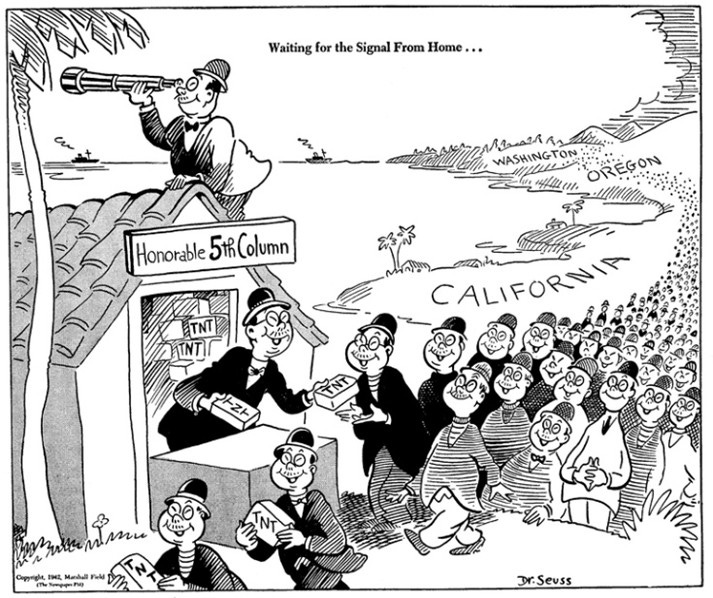

The cartoon above, drawn by Geisel in February 1942, has likely received more ire than any of his wartime works. In addition to featuring unflattering racial caricatures, it goes so far as to portray Japanese Americans as a fifth column—a group of people who undermine a nation from within, in this case on behalf of the Empire of Japan. Six days after its publication, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which began the internment of Japanese Americans.

While this illustration is a historical artifact—epitomizing a nation swept up in bitter racial vindication after Pearl Harbor—it was just as ignorant and offensive then as it is today. It reveals Geisel’s shortcomings—specifically, his failure to distinguish the beliefs and actions of the Japanese Empire and Japanese Americans.

It should be noted, however, that Geisel later recanted these myopic beliefs—1954’s Horton Hears a Who! is generally regarded as an allegory for Japanese occupation and an atonement for his earlier works; Geisel even dedicated the book to a friend from Kyoto.2

Lindbergh

Charles Lindbergh—like Geisel—was a strong-willed, immensely complex man. Though seldom mentioned today, he was greatly admired in his own time—an American icon who, regrettably, left behind a murky legacy.

Lindbergh is best remembered for his historic flight from New York to Paris in 1927, which made him the first person to fly non-stop across the Atlantic and granted him a level of fame and near-universal admiration unseen in American history—before or since.

He is also known for the horrific kidnapping and murder of his infant son in 1932, which spawned a colossal, grotesque media circus and directly led to suspected kidnappings across state lines becoming a federal crime via the “Little Lindbergh Law.”

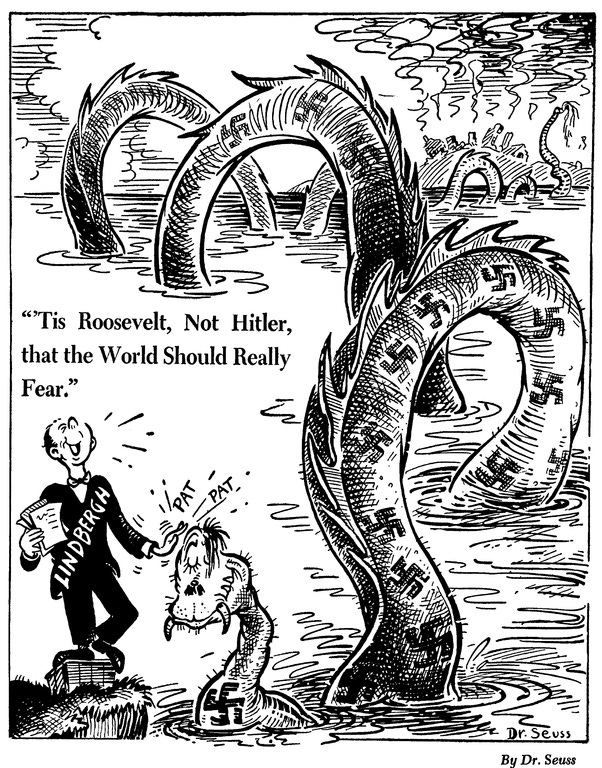

By the tail end of the ’30s, Lindbergh began—reluctantly—to dip his toes into politics. A staunch isolationist who believed American intervention in Europe would be costly and futile—and that a German victory inevitable—the famed aviator sought a way to communicate his message of neutrality to the American public. He leveraged his enormous celebrity to do so.

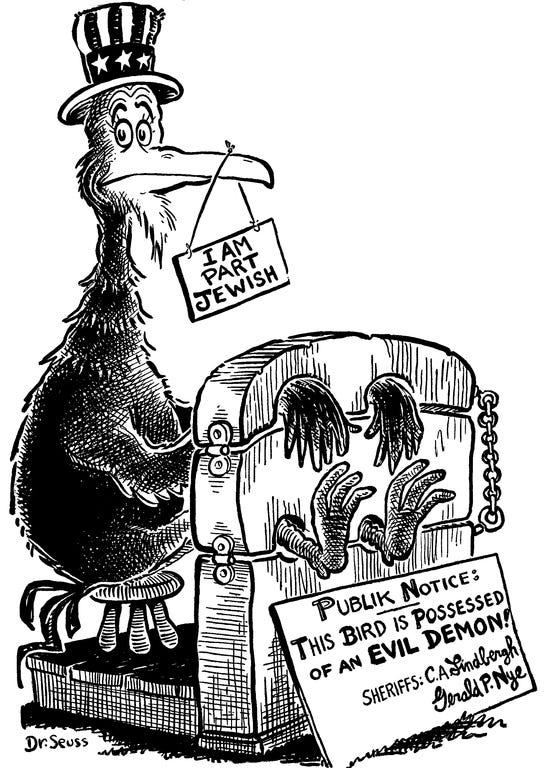

For the time in his life, the reticent Lindbergh began to willingly seek the spotlight, delivering his first of over a dozen nationally broadcast speeches just weeks after Germany invaded Poland. In this and subsequent speeches, he argued against American involvement and criticized the British government, Roosevelt administration, and those who controlled media—a clear dog whistle alluding to Jewish-Americans—for leading the nation down the path of war.

In September 1940, the America First Committee was formed by a group of prominent and well-connected law students at Yale University, with the goal of preventing American entry into the war. Early supporters included future Presidents Gerald Ford and John F. Kennedy; senators Burton Wheeler and Gerald Nye—Democrat and Republican, respectively—and Lindbergh himself, who would go on to become its primary spokesman.

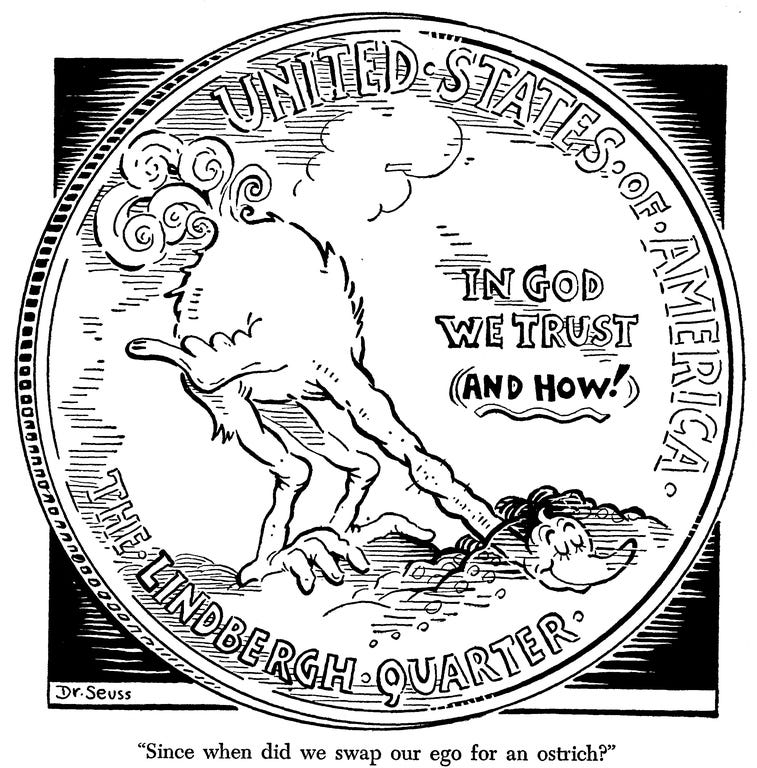

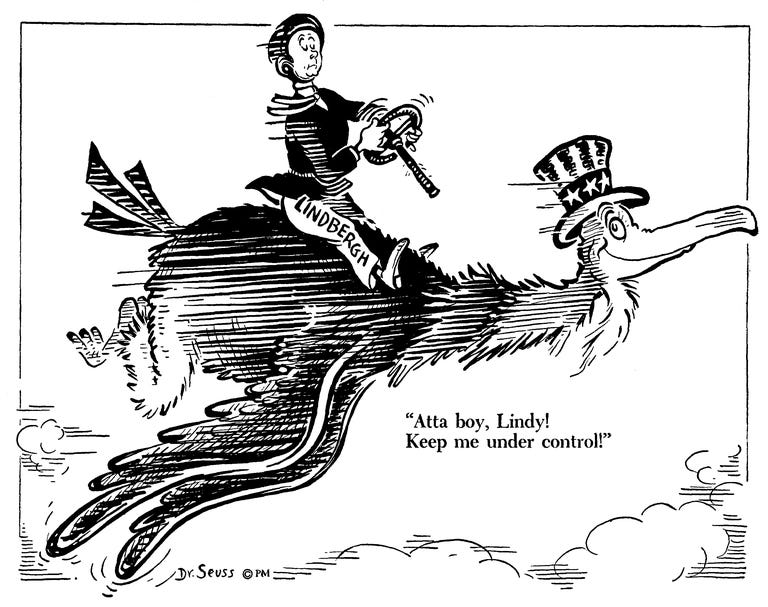

For Dr. Seuss, Charles Lindbergh was his biggest and easiest target—for both being universally recognizable and having no prior political experience. The Colonel fast became a punching bag for Roosevelt-leaning newspapers, like PM, despite delivering speeches that were undeniably thoughtful and empirically grounded.

Lindbergh, however, had his own problems beyond his otherwise logical addresses—most notably, a past soft spot for Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime that would later come back to haunt him. In October 1938, while reporting on the state of Germany’s Luftwaffe to the American military attaché in Berlin, he was awarded the Service Cross of the German Eagle by Field Marshal Hermann Göring, on behalf of the Führer.3

Although there’s no evidence Lindbergh considered this award any more significant than the thousands he had received since his historic flight, he nevertheless refused to return it—even after Germany invaded Poland the following fall. It was a damaging look for the aviator and only gave his opponents more ammunition.

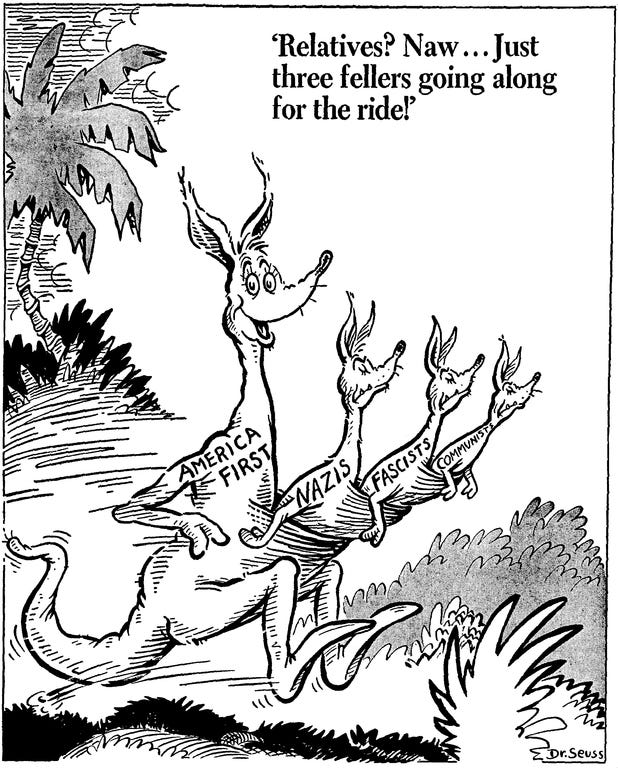

Geisel used his stinging wit to rebuke Lindbergh by name in fourteen of his cartoons—fewer mentions than only Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Vichy France’s Prime Minister Pierre Laval—and in many more he went after the America First Committee as a whole. Here are some of his finest punches:

It may be slightly disorienting to see such distinctly Seussian creatures laden with political messages—or even swastikas—but this was real, and it made Dr. Seuss a respected name in anti-fascist and progressive circles long before Horton Hears a Who!, The Cat in the Hat, and Green Eggs and Ham turned him into a global phenomenon.

The second-to-last cartoon—dated October 1st, 1941—has enjoyed remarkable longevity, still circulating on platforms like X and Reddit to this day. The quip “But those were Foreign Children and it really didn’t matter,” remains particularly poignant, just as relevant today as it was eight decades ago. What’s past is prologue.

Lindbergh never directly responded to Geisel’s attacks. In fact, from the moment he touched down in Paris in May 1927 until his death in 1974, he employed an “avoid-the-press” media relations tactic—rarely granting interviews and never responding to salacious news stories or the attacks of his critics.

However, since Lindbergh did travel to New York for America First Committee business during this period, it’s not a stretch to assume he was at least aware of Geisel’s less-than-sympathetic portrayals of him.

Result

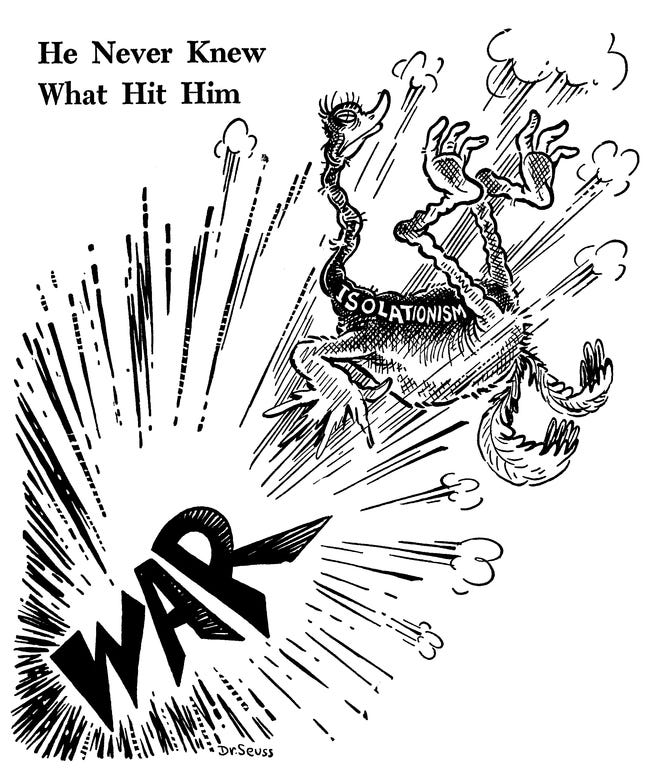

Well, as we all know, the America First Committee’s goal of keeping the nation out of World War II was not achieved. On December 7th, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched a surprise attack on the United States Navy fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and one day later, Congress voted nearly unanimously to declare war.

On December 8th, 1941, Dr. Seuss drew one of the most brazen “I-told-you-so”s of all time. The warnings against isolationism embedded in the cartoons he had spent the better part of a year drawing had come to fruition. He was proven right—America could not, despite its best intentions, keep itself out of war.

America First Committee was disbanded the following week, and its leaders—Lindbergh, Wheeler, and Nye—saw their reputations irrevocably damaged. The two senators would go on to lose reelection.

And Lindbergh, because of his outspoken views, would be denied the ability to serve in the Army Air Corps—though he would later unofficially participate in over fifty combat missions as a civilian advisor, even shooting down a Japanese aircraft.

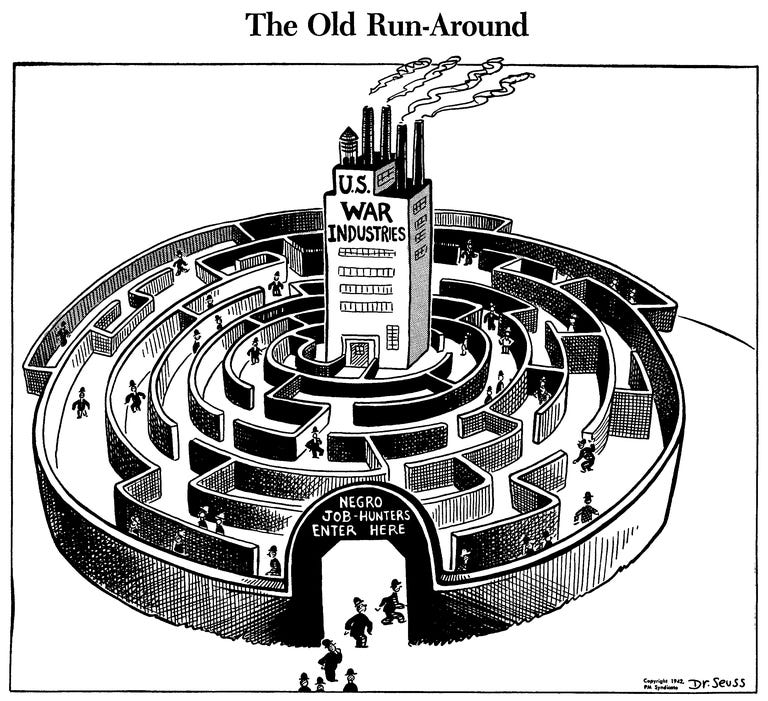

Dr. Seuss continued to draw for PM throughout 1942—mocking the defeats of Hitler, Mussolini, and Japan abroad, while boosting the war effort at home by urging rationing and the purchase of war bonds. He wasn’t merely a cheerleader, however; Geisel also attacked the barriers endorsed by the U.S. government that African Americans faced in contributing to the war effort (as seen in the cartoon above).

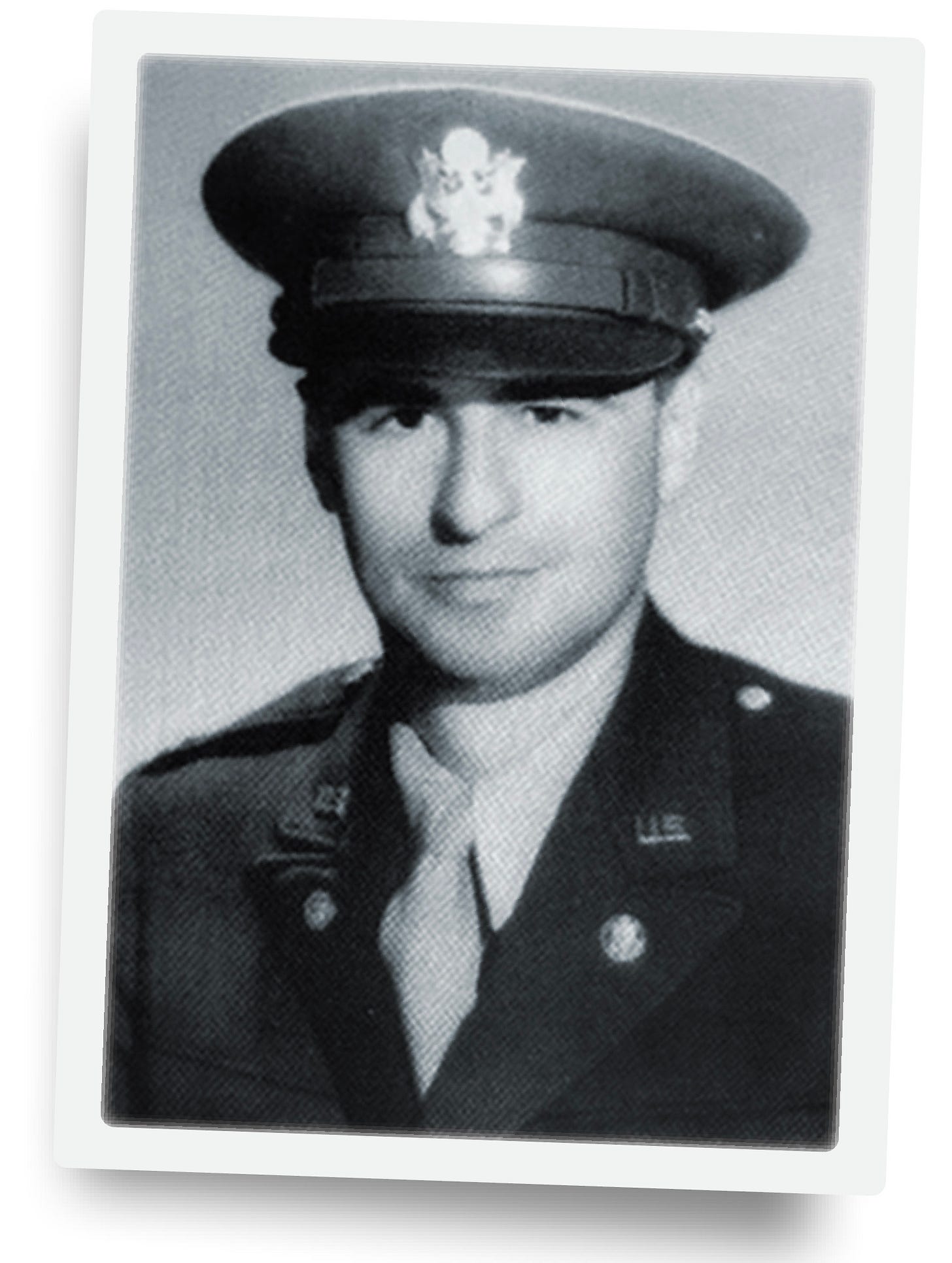

In 1943, too old for the draft, Geisel volunteered for the U.S. Army, where he commanded the Animation Department of its Motion Picture Unit. For the remainder of the war, he created training and propaganda films. He attained the rank of Major and was awarded the Legion of Merit for exemplary service.4

Legacy

As I mentioned earlier, Dr. Seuss enjoyed a very long, successful literary career following his cartooning work, which concluded with the Axis Surrender. Yet, aside from his indirect apology in Horton Hears a Who!, Geisel rarely acknowledged his WWII-era output.

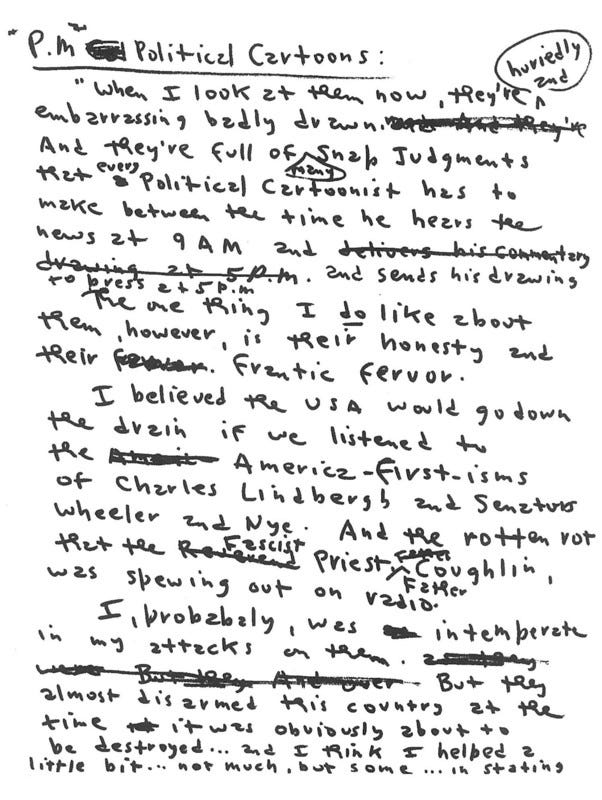

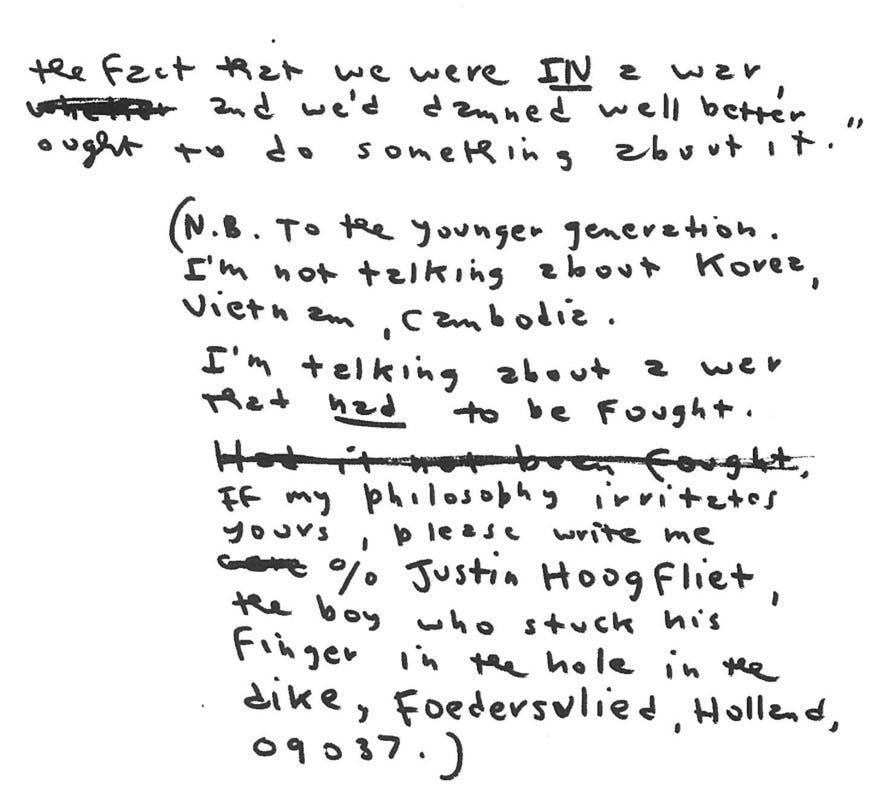

In a rare departure from this silence, he wrote a letter responding to a 1976 interview titled “The Beginning of Dr. Seuss,” published in Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. Because the article omitted his work at PM, the letter served as a kind of postscript.

He clearly didn’t take a calligraphy class while at Dartmouth. Still, despite its messy appearance, Geisel was thoughtful in reflecting on his work at PM—particularly his observation that the cartoons were “full of many snap judgments that every political cartoonist has to make between the time he hears the news at 9 AM and sends his drawing to press at 5 PM.”5

He had an “it is what it is” mindset—which isn’t entirely wrong. We were at war, after all, irrefutably fighting forces of pure evil. Yet even the otherwise progressive Geisel could be swept up in the wartime paranoia. That doesn’t excuse it or make it right—but it did happen, and it happened for a reason.

This was the last time Geisel spoke publicly about his wartime work; he passed away in 1991 at the age of 87. And while Dr. Seuss has faced considerable criticism in recent years for that chapter of his career, he deserves far greater recognition for his early and unwavering stand against fascism, antisemitism, racism, tyranny, and complacency—long before it was fashionable to do so.

https://library.ucsd.edu/dc/collection/bb65202085

https://www.openculture.com/2014/08/dr-seuss-draws-racist-anti-japanese-cartoons-during-ww-ii.html

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/lindbergh-fallen-hero

https://www.army.mil/article/53078/dr_seuss_the_cat_in_the_army_hat#:~:text=As%20a%20Soldier%20in%20the,to%20the%20Internet%20Movie%20Database.

https://apjjf.org/2017/16/minear