Black Celebration & Music for the Masses (Part 2)

Revisiting the second of the two sister albums of Depeche Mode's peak years.

In case you missed it, I highly recommend reading Part 1, which recaps Depeche Mode’s early career and their groundbreaking 1986 release, Black Celebration. Now, let’s continue…

Black Celebration was Depeche Mode’s creative breakthrough, signaling a stunning maturity in their musicianship and lyrical prowess—one that earned them their highest position on the U.K. album charts up to that point: #4.1 After embarking on the Black Celebration Tour in March 1986—a five-month international tour in support of the album—the band regrouped that winter and began work on what would become their sixth studio album: Music for the Masses. This album would prove to be a second kind of breakthrough for the quartet—their commercial one.

A Band on the Cusp

Prior to the release of their sixth album, Depeche Mode were synth-pop stalwarts in their home country and across continental Europe. Their first five albums had all performed extremely well there, but—as you may have picked up on through its omission from Part 1—this success did not extend to America.

Across the pond, Black Celebration barely cracked the top 100, peaking at #90 on the Billboard 200—a disappointing performance, especially compared to its predecessor, Some Great Reward, which reached #51. The band had scattered success in the U.S.—most notably the single “People are People,” a surprise hit that reached #13 on the Billboard Hot 100. However, they had never broken through, remaining confined to college radio stations, which were all the willing to play obscure, foreign acts.

Really, this time period—between March 1986 and September 1987—marked a band in purgatory: one that had achieved incredible artistic success, while the commercial success it warranted had yet to catch up. Depeche Mode were on the cusp of global stardom, and all they needed to seal it was one more great album, a worldwide tour—culminating in a performance so memorable it’s still talked about today—and a documentary film. Shouldn’t be too hard, right?

A Prophetic Title

As the story goes, when Depeche Mode sat down to name their sixth studio album, they landed on the title Music for the Masses—not as a cocky declaration of their popularity, but for precisely the opposite reason: they weren’t particularly good at making music for the masses.

The late Andy Fletcher said of the matter, “The title's ... a bit tongue-in-cheek, really. Everyone is telling us we should make more commercial music, so that's the reason we chose that title.”2

This joke may have been lost on some listeners as—ironically—this album would arguably become one of their most globally accessible releases and, discounting their New Romantic beginnings in 1981, feature some of their most pop-sounding songs.

The Differences

Of course, this accessibility did come at a cost: cohesion. Music for the Masses is more varied in tone than its predecessor, and that atmosphere—so crucial to Black Celebration—has largely been eroded, though it does resurface at several points, as we shall see. It’s still darkwave, just less dark and less solemn than before.

Music for the Masses is probably the most quintessentially Depeche Mode-sounding record. The band’s instrumentation was at the top of its game—thanks to Alan Wilder—and the production was remarkably polished, giving the album a sleek, dynamic sound. And with an extended break before Violator—which arrived in the spring of 1990—this was their final release of the 1980s—defining the sound they—and the decade itself—would be remembered for.

Lyrically, however, the album does seem like a step backwards for chief songwriter, Martin Gore—not a big one, just a baby step for now. His incredible storytelling on Black Celebration—as in “World Full of Nothing”—and Some Great Reward—most notably “Blasphemous Rumours”—isn’t quite matched on Music for the Masses. The songs and lyrics feel more superficial and agreeable, with less to discover on each relisten.

Now, this is not to suggest that Music for the Masses is a weaker release than the band’s two prior records simply because it features music that was radio-ready and destined to sell copies—with arguably less lyrical nuance. On the contrary, it actually holds its own quite well against Black Celebration: its songs are equally strong, though more sonically diverse. In fact, Music for the Masses stands as the second chapter in a trilogy—a trilogy of Depeche Mode’s no-skip records.

The Songs

Unlike Black Celebration, where the tracks stand on nearly equal footing, Music for the Masses reveals noticeable variation in quality—some songs clearly rise above the rest. I’ll highlight five tracks that I feel are the strongest—and an extra one just for fun.

Never Let Me Down Again

In the first five seconds alone, “Never Let Me Down Again” proves just how far DM has ventured from Black Celebration: an infectious synth-pop hook for the ages that faintly echoes their industrial roots on Construction Time Again—an instant classic.

It’s good, old-fashioned fun—not too heady—just a catchy song about “taking a ride with [your] best friend,” which, more precisely, means using drugs. Gahan’s vocals truly shine on this track—jubilant with a touch of paranoia—complemented by Gore, who once again steps into the background. The piano interludes are a delightful touch as well.

The Things You Said

While I doubt many fans would agree, “The Things You Said” is, in my humble opinion, the strongest track on the entire album. The first of just two songs Gore sings lead, it’s a slow-burning meditation on betrayal and disappointment—a reprieve from the album’s fast-paced surrounding tracks.

Gahan may possess the most powerful voice in the group, but this track would suffer without Gore’s gentle, shattered voice—the perfect touch. Its strikingly minimalist, carried through by just a bass synth and a piano. And its atmosphere—just as palpable as on Black Celebration—trades morbidity for pure, aching sadness.

Strangelove

The most recognizable—and commercially successful—track on Music for the Masses, “Strangelove,” like “Never Let Me Down Again” is pure, upbeat synth-pop steeped in perverse lyrics. It’s contradictory—like a cheerful Smiths song—and while this makes it feel slightly out of place on an otherwise bleak record, it nonetheless proves to be an engaging listen.

Released as the album’s first single, “Strangelove” reached #16 on the U.K. charts3 and #50 on the Billboard Hot 100. It was, indeed, a song for the masses—one that likely took inspiration from a certain 1964 Stanley Kubrick film.

Behind the Wheel

In my mind, “Behind the Wheel” serves as a sister song to—a continuation of—Black Celebration’s “Fly On The Windscreen.” Perhaps it’s even about the same vehicle. Built on a strong beat and a graceful, pulsating synth, the track is seductively dreary, like an odd dream.

A remarkable fusion of pop and one of Gore’s more introspective ballads, “Behind the Wheel” may encapsulate this album better than anything—striking that middle ground between accessibility and artistry. It was released as the record’s third single, with a B-side: a dark, synth reimagining of the ‘40s R&B classic, “Route 66.”

Nothing

This song is a deep cut, little remembered and relegated to the tail end of the record. Nevertheless, “Nothing” is a true hidden gem: catchy, groovy, incredibly danceable—it grows on you almost instantly. It’s part funk, part darkwave—and surprisingly well-suited for a road trip, as we shall see.

Gahan delivers his cleanest vocals on the album, with subtle backing from Gore. Never thought I’d hear “ooh ooh” in a Depeche Mode song this late to the game—but here we are…

Pimpf

“Pimpf” is the closer, an instrumental track—one more at home playing during a Dark Souls boss fight than at end of a pop record. It’s playfully glum and not to be taken too seriously—especially when the brightest song on the record, “Nothing,” immediately precedes it.

While “Pimpf” is arguably the least consequential song on Music for the Masses, it would go on to play an important role in Depeche Mode’s subsequent tour—and accompanying documentary.

Reception—Critical

Music for the Masses was released on September 28th, 1987 to critical acclaim and considerable fanfare. Smash Hits’ John Barty awarded the record a nine out of ten—Depeche Mode’s best review to that point—though The Smiths’ finale, Strangeways Here We Come, received a ten in that same issue.

Some of the vitriol that plagued Black Celebration, however, did carry over to this release—specifically, the sexual, slightly perverted lyrical undertones.

Melody Maker—which gave a particularly damning review to their last record—struck once again. Paul Mathur opened his piece with, “The peculiar Frenchman Bellia informs me that French youth refer to this comva as Depede Moche, which apparently means something like Dirt Paedophiliacs.”4 Needless to say, the rest of the review wasn’t very flattering…

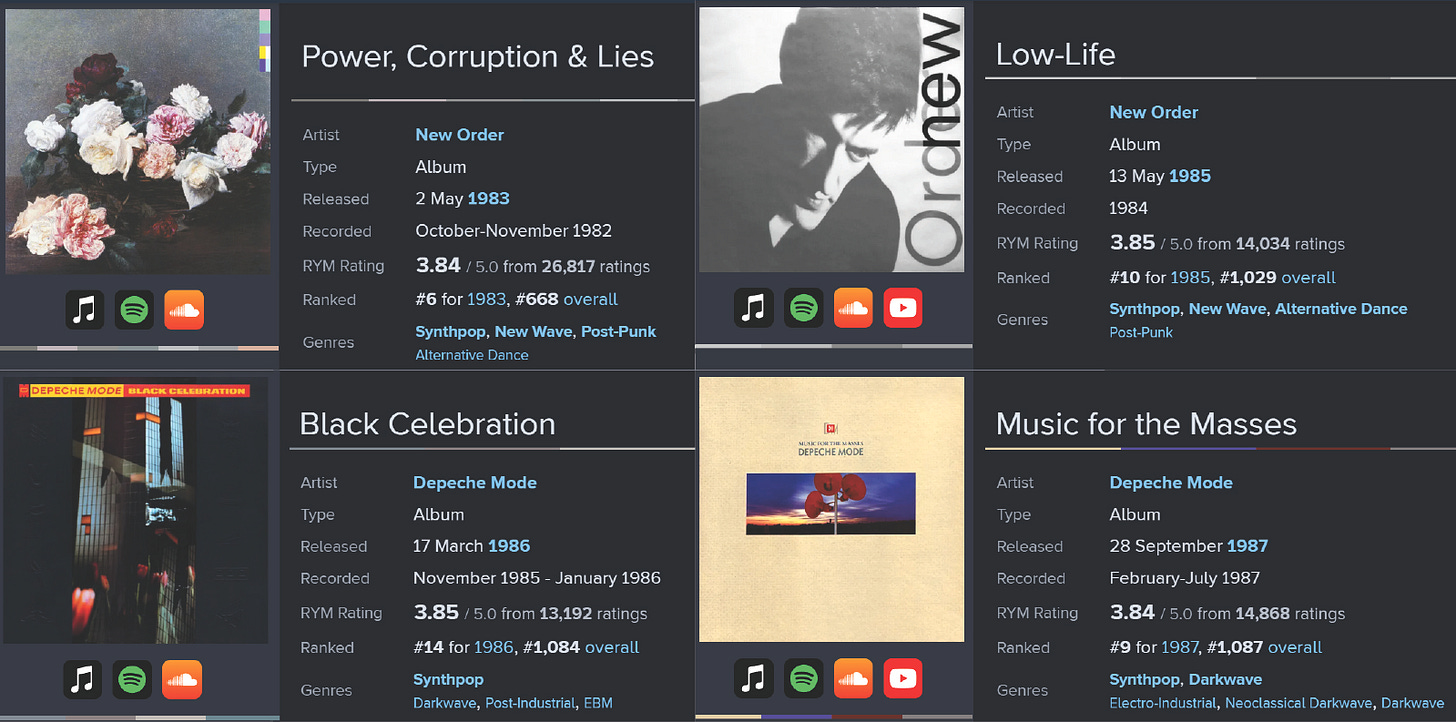

Turning to RateYourMusic—the ever-pertinent source of community-driven album ratings—we find that Music for the Masses holds a score of 3.84 out of 5, just a literal hair below Black Celebration, which received a rating of 3.85.

This opens Depeche Mode up to yet another comparison with New Order: two pairs of nearly identically rated, back-to-back studio albums. For DM, that would be Black Celebration (1986) and Music for the Masses (1987); for New Order, the pioneering Power, Corruption & Lies and the aforementioned Low-Life (1985)—see Part 1.

For these four decade-defining albums to end up with essentially the same rating is certainly an anomaly. Depeche Mode wins the tiebreaker, though—they didn’t need to take a year off, unlike New Order.

Reception—Commercial

Interestingly, Music for the Masses reached just #10 in the U.K.5—six spots below Black Celebration’s peak. It’s an oddity, and certainly a fluke, for a band that had otherwise consistently outdone themselves with each release in their home country.

On a related note, less than a year earlier, Vince Clarke’s new outfit, Erasure, scored a smash hit with “Sometimes,” the first single from their second album, The Circus, which went on to reach #6 on the U.K. album charts in April 1987.6 Depeche Mode was being outdone by one of its own founding members.

Abroad, however, Music for the Masses fared much better—reaching #2 in Germany,7 #4 in Switzerland,8 #7 in France,9 and even #35 on the Billboard 200, though that placement is somewhat misleading…

So, while Music for the Masses peaking at #35 on U.S. charts may not seem that extraordinary—Some Great Reward reached just #59—its staying power certainly was. The record stayed on the Billboard 200 for a whopping 59 weeks—over twice as long as Black Celebration.

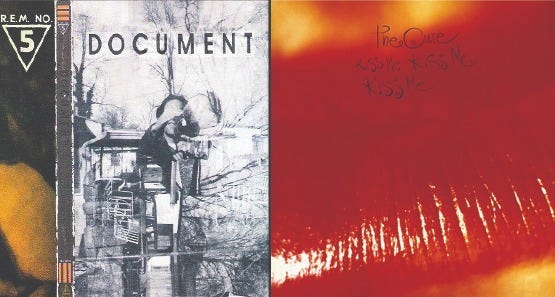

To put this feat into better perspective, I’ll compare it to those of two other alternative bands of the era: R.E.M. and The Cure—both of whom released an album in 1987.

R.E.M.’s Document, released on September 1st, peaked at #10 on the Billboard 200, dropping of the chart after 33 weeks.10 The Cure’s Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, released on May 26th, peaked at #3511—just like Music for the Masses—and stayed on the chart for 52 weeks.

Even though R.E.M. was far more established in the U.S. than The Cure—being from Athens, GA and all—their album peaked much higher and fell off the chart far quicker. The Cure—like Depeche Mode—cultivated their fanbase more slowly, but with great consistency and over a longer period.

For Depeche Mode, there was a catalyst to all this, as I mentioned at the beginning: a monumental tour—a tour for the masses—across the U.S., and a concert film documenting it all.

A Tour for the Masses

Depeche Mode began their Music For The Masses Tour on October 22nd, 1987—just weeks after the album’s release. It would prove to be their longest yet: 101 shows across three continents.

The band spent the first month touring across mainland Europe—where they had long drawn large crowds—before hopping the Atlantic in December for about a dozen U.S. dates. They then returned to Europe and continued on to Japan through the following April.

This is where the story gets interesting: Depeche Mode returned to the U.S., kicking off their second leg in Mountain View, California, on April 29th, 1988.12 Over the next two months, they zigzagged across the continent, playing thirty shows—while a film crew documented it all.

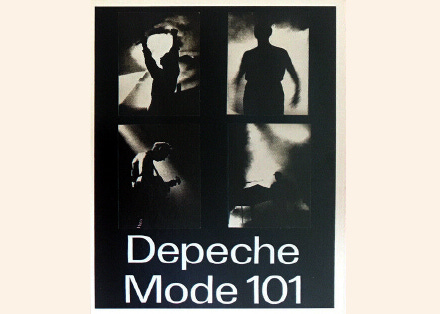

101

Depeche Mode could feel themselves on the verge of something special in the United States—finally breaking free from the confining moniker of alternative music and stepping into the mainstream. That’s why they decided to tap renowned documentarian D.A. Pennebaker to capture the moment for the big screen.

As a film, 101 offers an incredibly gripping look at the dynamics of a band in their absolute prime—rapidly approaching their creative peak as their commercial success begins to catch up with them right before their eyes.

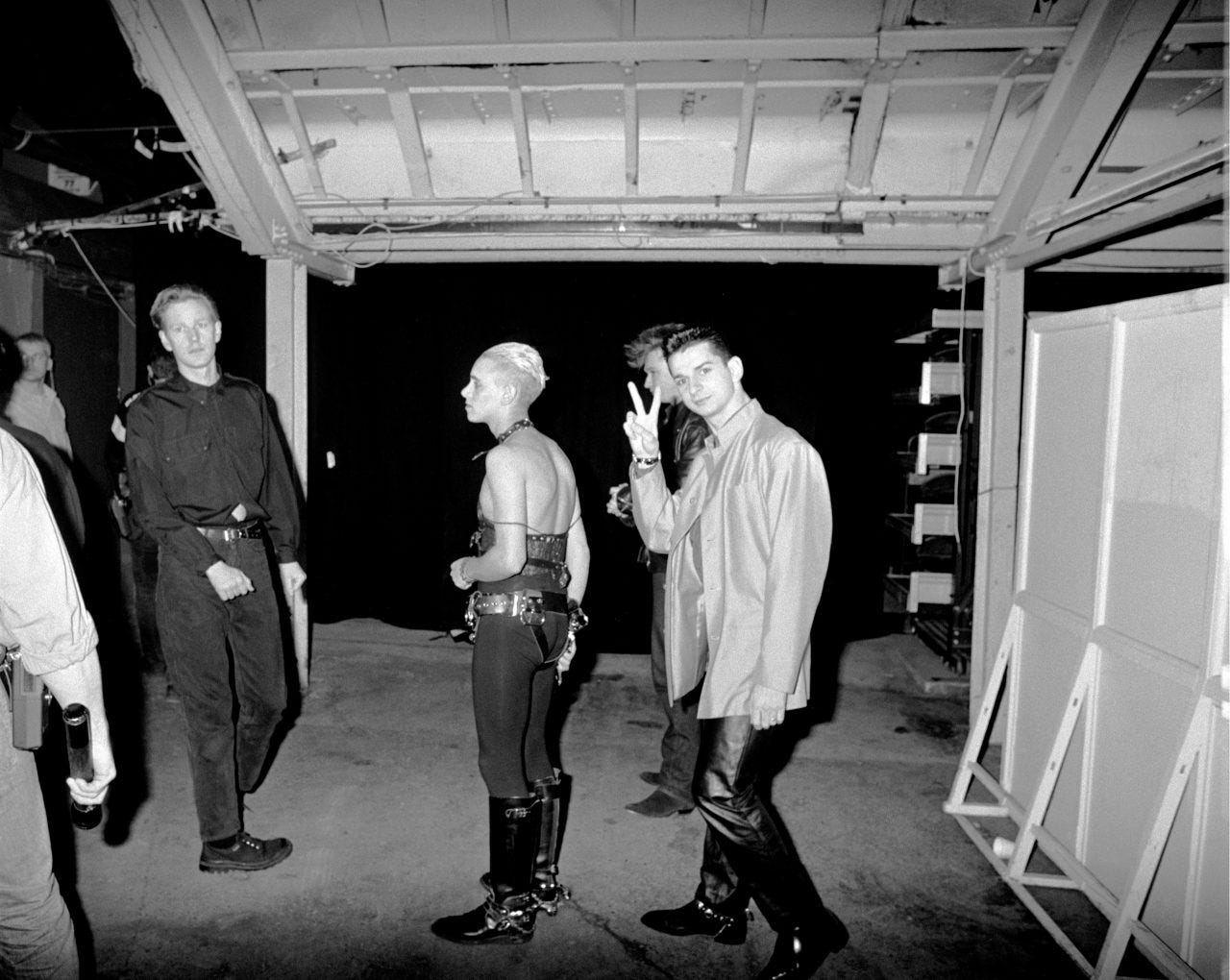

It’s immediately striking how a band with no traditional instruments—just synths and drum machines—can be so engaging live. Gahan, neither a writer nor a musician, makes up for it by fully embodying his role as DM’s frontman.

He carries immense pressure: Gore, Wilder, and Fletcher remain motionless, playing their synths in the dimly lit background—leaving him to strut and dance alone in the spotlight. It’s an interesting sight to see Gore like this—in the shadows—while Gahan receives the applause, performing the songs that Gore had wrote.

101 is a bit of a medley—a hodgepodge of concert footage the final thirty U.S. performances, scenes of the band on the road, DM’s management trying to prop up ticket sales, and a group of contest-winning fans traveling across the country to see the band’s last show.

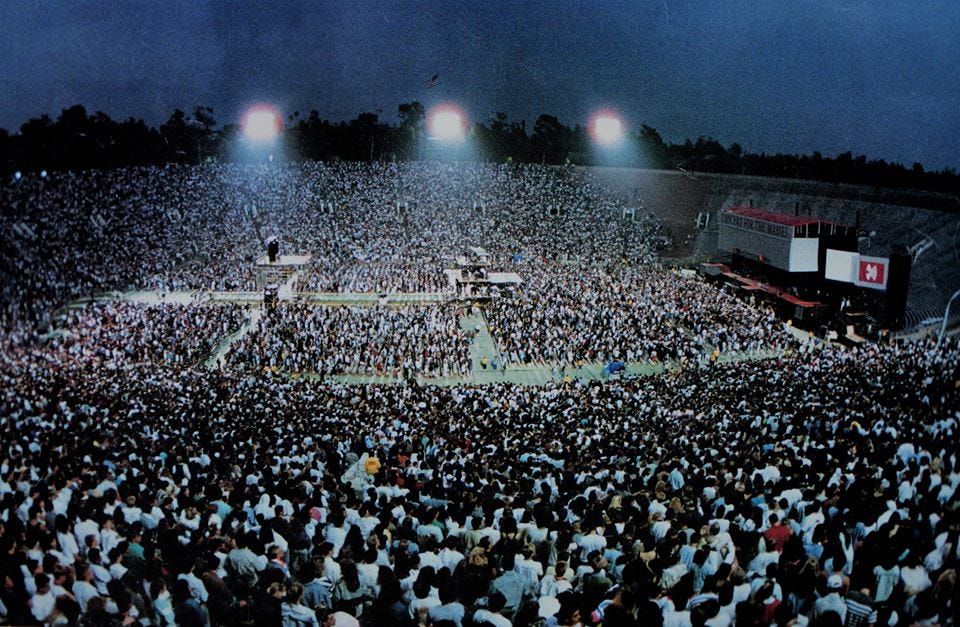

This 101st and final show—at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California—is the emotional arc of the film, and the source of its name: can Depeche Mode sell it out?

Predicting Personalities

Along the way, we learn a lot about the personalities of the band members. The first two were more predictable—the last pair, however, were quite surprising.

Dave Gahan is the boisterous, high-spirited one—bringing the fun and excitement, cracking jokes, but also snapping at the crew on occasion. He tells a story about an altercation with a cab driver, whom he gutlessly attacks from behind—it’s unclear whether this was meant as a joke or not.

Martin Gore is the shy, thoughtful, most interestingly-dressed one—slightly uneasy throughout the filming, yet willing to show his comic side from time to time. At one point, Gahan trades the spotlight with him during “The Things You Said,” which Gore performs while nervously leaning against a raised platform, certainly not matching the frontman’s swagger.

Alan Wilder is the knowledgeable one—the classically trained musician—and proves his skills early in the film, demonstrating the complicated keyboard and drum pad settings required to play “Black Celebration” live. He comes across as the most intelligent of the bunch, aside from Gore, perhaps.

And Andy Fletcher—“Fletch”—he’s the ambiguous one. He openly admits that his role in the band is less categorical than the rest: “Martin’s the songwriter, Alan’s the good musician, Dave’s the vocalist, and I bum around,” he says. But Fletch’s job was a noble one: to be the glue—holding Depeche Mode together and keeping the other three from being at each other’s throats.

The KROQ Factor

In Nashville, Depeche Mode perform to a crowd of just 2,000—the concert footage showing an auditorium noticeably below capacity. Funnily enough, the band was fairly pleased with the turnout, having expected even fewer people to show—a modest bump saved by last-minute promotions from their management.

This was a recurring theme in the film: Depeche Mode suffered greatly from infrequent radio play across America. In a southern, conservative market like Nashville, this translated to dramatically fewer ticket sales.

One saving grace of this tour stop was the band’s visit to a country record store, where Martin Gore is shown carefully examining a Johnny Cash cassette—the legendary musician who would later cover Gore’s “Personal Jesus” in 2002.

Unlike in Nashville, on the West Coast—specifically Los Angeles—Depeche Mode had been receiving considerable airplay on the popular radio stations KROQ, which championed their more alternative strain of synthpop. Stations in other markets began to follow suit, and with greater airplay came significantly higher ticket sales.

The Finale

The documentary ends on a high note: June 18th, 1988, when Depeche Mode performed to a sold-out crowd of over 65,000 fans at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena.

Waiting until after sunset and for total darkness to take the stage, the band powered through a medley of tracks from their three most recent records—three phenomenal, groundbreaking albums. They faced a passing thunder storm—including a nearby lightning strike, met with screams, during “Something To Do.”13

Their best performance of the night, in my opinion, was “Blasphemous Rumours,” which so fittingly occurred through a black curtain of drizzling rain. Even through the film cameras, the emotion of the crowd is palpable.

Depeche Mode ended their second and final encore of the night with two songs: “Just Can’t Get Enough” and “Everything Counts,”—hits from their early days. It was a fitting way to end what was, in many ways, the singular zenith of their career—a reflection of how much they’d grown in just eight short years.

Dave Gahan ended their final song by leading the audience of 65,000 in singing the chorus: “The grabbing hands grab all they / Everything counts in large amounts,” pausing to gaze in genuine awe at the spectacle, beaming all the while.

Finally, Dave Gahan, Martin Gore, Alan Wilder, and Andy Fletcher walked off stage to a deafening final applause from an audience absolutely gripped from start to finish. Depeche Mode had finally made it—and their best was yet to come.

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/depeche-mode-black-celebration/

https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/music-for-the-masses-depeche-mode-35/

https://www.officialcharts.com/songs/depeche-mode-strangelove/

https://depechemodefile.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/rubber_bullets.jpg

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/depeche-mode-music-for-the-masses/

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/erasure-the-circus/

https://www.offiziellecharts.de/charts/album-details-612

http://swisscharts.com/album/Depeche-Mode/Music-for-the-Masses-612

https://web.archive.org/web/20160201073400/http://www.infodisc.fr/B-CD_1987.php

https://www.billboard.com/artist/r-e-m/chart-history/tlp/

https://www.billboard.com/artist/the-cure/chart-history/tlp/

https://dmlive.wiki/wiki/Category:1987-1988_Music_For_The_Masses_Tour

https://dmlive.wiki/wiki/1988-06-18_Rose_Bowl,_Pasadena,_CA,_USA#Set_list