Soul Mining and the Art of Introspection

A look back at the early career of The The's auteur, Matt Johnson, and the band's seminal 1983 debut.

Music has the incredible power—more so than perhaps any other facet of life—to attach itself to a particular time, place, emotion, or person, without any conscious thought or predetermination. It’s an extraordinary phenomenon: one that allows the visceral transfer of experience from one person to another.

Those who create music often embed their own lives—circumstances, experiences, feelings, and beliefs—into their work. It retains a distinct, personal meaning for them, perhaps one they hope to evoke in others. Yet so often, it’s co-opted—millions of times over—by the listeners who reshape it to fit entirely different meanings, molded to their own lives.

This is an article about introspection and music, which—at its purest, I believe—serves as a metacognitive exercise for its creator. Of all the musical works that I’ve experienced, one stands above the rest in this regard: Soul Mining, a 1983 post-punk record by English band The The.

One Man Band

A self-examining creative work is something of an autobiography—one of a person’s psyche rather than their experiences. Music rarely achieves this quality, in great part because bands—as opposed to solo artists—consist of multiple competitive, often rivaling psyches.

I called The The a band—which is technically correct—but like Nine Inch Nails or Tame Impala, it’s the creative vision of a single person: Matt Johnson.

The The’s brainchild was born in London in 1961 and came of age in the late ‘70s—an era when few opted to pursue music entirely on their own. Among the rare exceptions were Gary Numan, Thomas Dolby, and Howard Jones—though their work leaned more toward homogenized synth creations.

“An Emotional Hot House”

However—Johnson didn’t get his complete start unaided. He grew up playing music with friends, performing in bands from the age of eleven. But as he left school, the young adult went through a reclusive period, what he described as “an emotional hot house experience.”1

Johnson spent many months indoors, in a room piled high with books, music, and—most crucially—tape recorders. When he did venture outside, it would be for lengthy, solitary walks, allowing him plenty of time to think, unperturbed.

“That period, really, really changed me,” says Johnson. “I started being able to see things I hadn’t previously been able to see and hearing things I previously hadn’t been able to hear. I started sensing things that I hadn’t realised were there before. And this tremendous infusion of energy had to find an outlet somewhere.”

This was the genesis of an illustrious musical career.

Musique Concrète

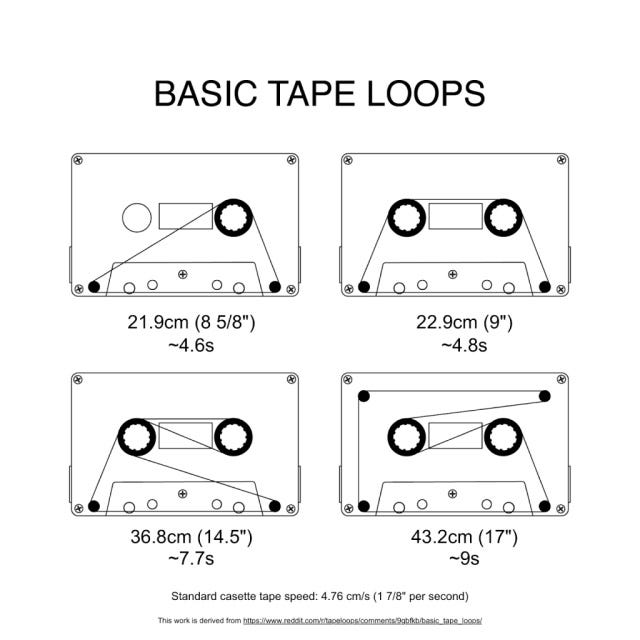

Already a seasoned musician, Johnson—armed with his family’s reel-to-reel tape recorder, and later an Akai—poured his spirit into making music. But early on, these were really just experiments with sound. Through the creation of tape loops, he discovered he could make intricately layered music that had previously only been possible with a band.

This process was heavily inspired by musique concrète, a mid-20th century music genre that “involves recording, manipulating, and assembling environmental sounds—both natural and synthetic—into compositions that are played through speakers rather than traditional instruments.”2

Essentially, Johnson would record small fragments of instruments or found sounds onto cassette tapes, then slice and reassemble them to create a short strip of tape that looped indefinitely (see above). These loops could then be combined on a multitrack reel-to-reel recorder—a precise, tedious process.

God only knows what this imaginative kid could’ve done if GarageBand had existed in 1979…

Early Creations

With his do-it-yourself approach and propensity for lonesome freewheeling, Johnson created several full-length albums—the first of which, See Without Being Seen (1979), when he was just 16 years old.

This album is rough, to say the least—recorded in the basement of his parent’s pub.3 But despite of the low-quality production, its tracks were on the cutting age for the late ‘70s: moody post-punk creations echoing the band at the genre’s forefront—Joy Division.

Now, for an group of established twenty-something-year-olds, See Without Being Seen wouldn’t have been looked on too favorably. But for the 16-year-old Johnson—whose first foray into recorded music proved a thoughtful, fiercely original record—an exception can be made.

Unfortunately, the teenager never officially released the record, though he did sell a limited number of cassette copies at his early gigs. The master tape would be lost for many decades, until it was found, restored, and formally released in 2019.

It was around this time that—perhaps feeling slightly bored of working all by himself—Johnson placed an advert in NME, “looking for likeminded fans of the Velvet Unground, the Residents, and Throbbing Gristle to form a band with him.”4 This would mark the formal birth of The The.

The The & Burning Blue Soul

The The’s first formal lineup consisted of Johnson on vocals, electric piano, guitar, and tapes, and Keith Laws—who had responded to Johnson’s ad—on synthesizer and tapes.

Laws was the one to come up with the name “The The,” which Johnson agreed to specifically to confuse people with its genericness. Try searching “The The the band” on YouTube and you’ll understand exactly what I mean.

The duo quickly partnered with the renowned indie label 4AD and recorded their first release: a two-song single featuring “Controversial Subject” and “Black and White,” released in August 1980. It failed to chart.

Laws left the band soon after and went on to pursue a successful career as a psychologist and later became a professor of neuropsychology.5 This left Matt Johnson, on his own once again, to continue The The as a solo project.

Burning Blue Soul

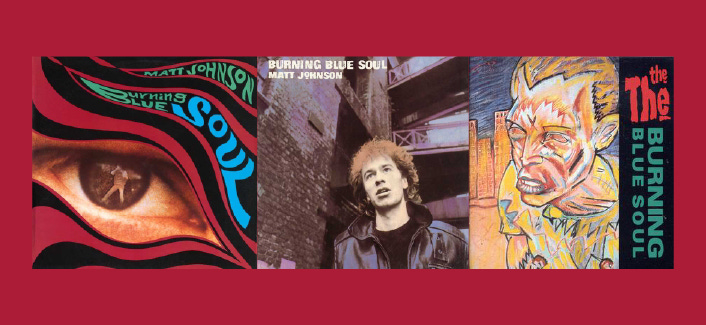

Johnson, undeterred, continued his partnership with 4AD and released his first true studio album, Burning Blue Soul, in September of 1981—under his own name.

This record has aged remarkably well. It remains highly experimental, yet benefits from its modestly increased recording budget: £1,800. Johnson was living on welfare at the time and had to “beg, steal, or borrow time at the studio”6—a worthy endeavor, indeed.

The sound is strikingly sparse—like it was captured in an grand, echoing cathedral. Johnson’s vocals are isolated, the guitars are heavy with distortion, the bass slick and fluid, and the background brimming with the found sounds of musique concrète.

Lyrically, there are traces of Johnson’s modus operandi: stream-of-consciousness writing drawn from the annals of his mind. Yet on most of Burning Blue Soul’s tracks, the vocals take the backseat—yielding to the dominance of experimental instrumentation and noises.

This album could really warrant an article of its own, and arguably has a sound just as unique as its successor, Soul Mining—though one grittier and more despondent.

It’s certainly a harder to pigeonhole than Johnson’s latter output—melding elements of pop, post-punk, new wave, gothic rock, and even psychedelic. A true oddity lost to time, yet sonically untethered from it.

Burning Blue Soul failed to chart, though it was reissued twice: first in 1983, with an alternate cover, and again in 1993—this time with yet another cover and under the “The The” name (see above).

I like to think of this album as a trial run for Johnson—building the artistic confidence and distinct sound that would fully emerge two years later, on his next project: Soul Mining.

Making A Masterpiece

Between the recording of Burning Blue Soul in early 1981 and Soul Mining in 1983, the music world underwent a major shift: the rise of synthpop.

1983 was the year of Power, Corruption & Lies, after all—a record that saw Joy Division’s successor, New Order, make the leap from post-punk into electronica.

It would be erroneous to claim that Johnson didn’t take notice of these trends. They greatly influenced the production of The The’s debut—and his second—studio album: the guitars were out, and the synthesizers were in.

Case in point: Johnson had originally intended an as-yet-unreleased album, Pornography of Despair, to be his sophomore effort—but he scrapped it in the winter of 1983.

Bootlegs of this record can be found online, including several tracks that eventually made their way onto Soul Mining. And despite the low fidelity of these recordings, it’s an intriguing listen—a punkier version of Soul Mining, before it received a clean coat of synth polish.

The Writing Process

Johnson and The The signed a record deal with CBS, which provided him, for the first time in his adult life, financial security—via an £80,000 advance.7

He traveled to New York to record material for what would become Soul Mining, but after a series of poor, drug-fueled decisions, he returned to London effectively empty-handed.

So, with the record company breathing down his neck, Johnson took to his apartment, lying on the floor for hours on end, where he wrote the record.

It was likely this environment—left entirely alone with his thoughts—that allowed the self-awareness so openly expressed on Soul Mining to percolate.

When it came time for recording, Johnson received help from some of his heavy-hitting musician friends—including Orange Juice’s Zeke Manyika, Squeeze’s Jools Holland, and synth pioneer Thomas Leer.

Johnson, however, wrote the music and lyrics for all of Soul Mining’s seven songs, with the notable exception: a certain iconic piano solo—but we’ll get to that.

The Songs

Since Soul Mining has a mere seven songs—none of which are weak—we’ll discuss each of them in detail.

I’ve Been Waitin’ for Tomorrow (All of My Life)

There’s one word to sum up Soul Mining’s leadoff track: frantic.

Just the opening line—“I'm hiding in the corner / Of an overgrown garden / Covering my body in leaves / And trying not to breathe”—is sarcastically stupid enough to make you question Johnson’s sincerity.

“I’ve Been Waitin’ for Tomorrow” continues like this for about five minutes, with an aggressive drum machine beat and pulsating synthesizer—and plenty of musique concrète found sounds to boot.

I think by about the fourth minute, when Johnson decides to end the track by repeating “My mind has been polluted / And my energy diluted” about a dozen times, he finally convinces me that he’s serious. But it’s all in good fun.

This song’s lyrics read like a bunch of non-sequiturs—intrusive thoughts all themed around how much of a failure your life has been, delivered with impulse. Fun stuff, indeed.

This is the Day

The name of this song sounds awfully familar, doesn’t it?

If the crux of the last track was the realization that you’ve been squandering the precious gift of life, then “This is the Day” is the ultimate creation in this meditation—with a positive spin, too.

So, much can be said about this song: that feathery synth fade-in, accordion hook, and graceful fiddle—and the lyrics.

“This is the Day” is about living in the past—letting your memories rule over and dictate your life.

It’s not meant to depress, like “I’ve Been Waitin’ for Tomorrow,” but really is a call to action: “This is the day / Your life will surely change / This is the day / When things fall into place.”

There are two lyrics that really stand out as profound—communicating an almost universal feeling with such incisive clarity:

“You’ve been reading some old letters / You smile and think how much you’ve changed / All the money in the world / Couldn’t buy back those days”

“You could’ve done anything / If you’d wanted / And all your friends and family / Think that you’re lucky / But the side of you they’ll never see / Is when you’re left alone with the memories / That hold your life together like glue”

It reveals a fundamental truth about nostalgia—its blinding effect—and the slow-fading former glory that quietly steers our worlds.

It’s all phrased in the third person, yet it reads too pointedly to not carry personal truth. This is Johnson’s meditation on his life thus far—the emotional hothouse he once inhabited, and all.

The Sinking Feeling

“The Sinking Feeling” appeared in post-punk demo form on Johnson’s Pornography of Despair. For Soul Mining, the track has been stripped down, opening with a lone pulsing synth and a subdued Johnson narrating his dysfunctional existence.

Eventually, the song kicks into gear, bringing in a full band—with real instruments, I might add—and the refrain: “I'm just a symptom of the moral decay / That's gnawing at the heart of the country.”

Personally, I feel the demo version was stronger, with its heavier, synthesizer-free sound. Nevertheless, “The Sinking Feeling” is a solid—albeit potentially forgettable—track, sandwiched between the album’s two best songs.

Uncertain Smile

This was the song that put Matt Johnson and The The on the map—their first charting single. “Uncertain Smile” was originally conceived as a demo on Pornography of Despair called “Cold Spell Ahead.”

Like “The Sinking Feeling,” it was originally guitar-driven. But while that transformation arguably detracted from the former, it greatly enhanced the latter. “Uncertain Smile” was reshaped around an eclectic mix of instruments: acoustic and electric guitar, synth strings, drum machine, grand piano, and—most unexpectedly—a xylorimba, the xylophone’s extended cousin.

These instruments are gradually layered—one atop the other—until the climax of this nearly seven-minute song, when the grand piano enters for a legendary solo, performed by Jools Holland of Squeeze. It goes from being an austere synthpop tune to a dynamic concerto—the drum machine as its only constant throughout.

Despite being the second longest track on the album, “Uncertain Smile” has the fewest lyrics: just two verses and a twice-repeated chorus. It’s a simple but powerful song: “Uncertain emotions force an uncertain smile.”

Twilight Hour

“Twilight Hour” resembles a polished rendition of one of Johnson’s early tape loop experiments—this time with a budget for violin and cello. It has a prolonged intro: lush in texture, but lacking in excitement, which returns periodically throughout the track.

The song recreates the tension of someone waiting at home for their lover to call—the growing panic as the time ticks by. Johnson delivers his most varied vocal performance here, trading his usual dour tone for a slurred, whiny delivery. It’s a fitting choice for the mood, though certainly not his strongest.

It’s told like a story, but really reads more like the paranoid thoughts of the main characters, jumping to brash conclusions as he waits by the phone: “She can't leave you now - you've given up all your friends / You’re relying on her—for your independence / She can't leave you here—alone & defenseless.”

Johnson’s increasingly ludicrous thoughts against a wall of jolly synthesizers is an odd, but effective juxtaposition. “Twilight Hour” may be one of the—if not the most—forgettable track on Soul Mining. But its quirks help illustrate why Matt Johnson remains a one-in-a-million artist.

Soul Mining

The album’s title track is also its most unassuming. “Soul Mining” is an incredibly reserved piece, with a peaceful, almost meditative atmosphere—enhanced by Johnson’s near-whispered vocals.

Of course, in true The The fashion, the lyrics and the music are at odds with each other. “Something always goes wrong when things are going right... / You've swallowed your pride—to quell the pain inside.”

Eventually, drums and a more powerful, hypnotic synth kicks in, adding a charge but largely preserving the restful atmosphere.

“Soul Mining” isn’t as dramatic as “Twilight Hour”—and that’s a plus, in my opinion. This track is often overlooked for its lack of a hook or gusto, but it’s an engrossing listen, with poignant lyrics, delivered with nonchalant grace.

Giant

The album closer, “Giant,” is a monster of a track—clocking in at nearly ten-minutes. Some versions of Soul Mining—including the U.S. CD release—add a ninth track, “Perfect,” to finish the album. And even though it’s a solid song, it doesn’t do the job nearly as well.

“Giant” charts an unraveling of the self against a worldly beat and fluxing synths, as Johnson opens: “The sun is high and I'm surrounded by sand / For as far as my eyes can see.”

The song continues to layer on new sounds as Johnson grows increasingly frenzied, until he’s repeating, ad nauseam, “How can anyone know me / When I don't even know myself?”

In the final three minutes, Johnson’s refrains give way to African-inspired tribal chanting—lifted by Kate Bush in her 1985 hit “Cloudbusting”—which plays off this extemporary record with an unexpected, yet admittedly uncanny, precision.

While a little self-indulgent, “Giant” captures The The at their most mesmeric.

Reception

Soul Mining was released on October 21st, 1983 to largely positive reviews and modest commercial success. The record peaked at #27 on the U.K. charts, where it remained for five weeks.8

The album’s three strongest tracks—“This is the Day,” “Uncertain Smile,” and “Giant”—were released as singles, all peaking between #65 and #80. Neither the album nor its singles charted in the U.S.

Despite being signed to the major label CBS and producing more radio-friendly material than his debut effort, Burning Blue Soul, Johnson maintained the underground, unacknowledged genius mystique with Soul Mining that defined his early career.

And despite finding far greater chart success with a poppier sound on his subsequent releases, Johnson would never eclipse the creative genius of The The’s first album. In fact, the band’s two most recognizable and beloved songs—“This is the Day” and “Uncertain Smile”—came from Soul Mining, not from his higher-performing records.

Critical Acclaim

Critically, Soul Mining was an immediate triumph in England—and even made ripples across the pond in America. It placed third on Melody Maker’s Best Albums of 1983 list, ahead of heavy-hitters like New Order’s Power, Corruption & Lies, Tears For Fears’ The Hurting, and R.E.M.’s Murmur.9

The magazine’s Steve Sutherland offered an incisive and glowing assessment, writing “There’ll be times when it will sound obscenely close to the bone, as if [Johnson] were invading and defiling your most private thoughts and emotions … In other words, you’ll use Soul Mining as a barometer to your day.”10

In America, while not garnering widespread public attention, Soul Mining received considerable praise from critics—including Rolling Stone, which noted: “What distinguishes Johnson from the rest of the British synth-pop horde is his sense of structure and his unerring ear for sonic definition.”

The review also pointed to a broad weakness of the record: “If there's a problem, it's with Johnson's obsessively self-absorbed lyrics … Youthful angst and anomie are fine in their place, but not all over the place.”11

Relevations

Narcissism—it comes with the territory of introspection, and Soul Mining, more so than any record I can name of the top of my head, presents an artistic product so unabashedly self-obsessed.

One of Soul Mining’s most impressive feats is that in its seven tracks, Johnson only drops the word “love” a singular time—on “I’ve Been Waitin’ for Tomorrow (All of My Life)”: “And the cancer of love has eaten out my heart.”

Of all the universal themes of art, across cultures and ages, love is second to none. Yet it’s admittedly a crutch for artists—a subject matter guaranteed to elicit at least some response from listeners.

Matt Johnson’s deliberate departure from this norm yields both challenge and triumph. When his songs strays from typical form—grounded in events or emotions—and instead become an amalgamation of swirling thoughts and impulses, he achieves an artistic state worthy of a new genre: the “existential blues.”12

The Mask of Pouting

Johnson’s parochialism makes it harder for him to connect with others through his music—or gain their sympathy. There’s something overtly fretful about Soul Mining, as if it’s airing the complaints of a spoiled child.

But really, aren’t we all a little whiny in our minds—quietly fuming over the most trivial disapprovals, even when they never quite reach the surface?

Soul Mining is, after all, a terribly pessimistic album. And though Johnson’s lyrics embody a litany of negative emotions: sorrow, irritation, bitterness, and neuroticism—it feels less like a product of depression than of passion.

What emerges is the human propensity to overreact in the moment—a quickly passing panic, raw and unfiltered. And for this reason, Johnson manages to skirt the tortured genius archetype—unlike Kurt Cobain or Brian Wilson.

A Lasting Obsession

As for his triumphs, Matt Johnson remains on the outside looking in—and Soul Mining is his insular masterpiece. Untethered from people, places, or events that fade with time, its seven tracks feel no more or less relevant today than at their birth over 42 years ago.

Johnson’s songs are remarkably mature for having been written by a 21-year-old. They speak not with youthful bravado, but with the quiet introspection of an aged man reflecting on his life—did he make the most of it?

The The attracts a certain kind of listener: the compulsive thinker. And I don’t mean thinker in the intellectual sense of the word—but in the obsessive one. The kind of person whose mind simply cannot be coaxed into rest, as Johnson demonstrates through his frantic overanalysis of daily existence.

With Soul Mining, there’s a story to piece together—a common thread to follow—in life’s undoing. It’s like scattered shreds of paper—words that Johnson must painstakingly reassemble—that once held his life together… like glue.

https://thequietus.com/interviews/matt-johnson-interview-soul-mining-the-the/

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/music/musique-concrete

https://www.thethe.com/product/see-without-being-seen-cd/

https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2017/may/31/the-the-10-of-the-best-matt-johnson

https://herts.academia.edu/KeithLaws

https://www.uncut.co.uk/features/somewhere-between-pure-euphoria-and-terrible-insecurity-an-interview-with-the-the-s-matt-johnson-6930/

https://www.electronicsound.co.uk/features/long-reads/matt-johnson-the-soul-miner/

https://www.officialcharts.com/artist/19893/the-the/

https://music.co.uk/rocklist/mmpage.html#1983

https://dohmannaudio.com/music-recommendations/the-the-soul-mining/

https://web.archive.org/web/20100209065042/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/thethe/albums/album/224874/review/6067656/soul_mining

https://www.musicistoblame.co.uk/2021/10/the-artists-that-time-forgot-the.html