Talk Talk and the Cost of Creativity

A retrospective on a transcendent New Wave band that rewrote the rules—and then walked away.

A pattern can be observed in most successful bands: they experience a period of creativity and individuality in their work, which—more often than not—coincides with their greatest commercial success. This is known as an imperial phase. The term was coined by Neil Tennant—the lead singer of the Pet Shop Boys—in 1988, in reference to his group’s own commercial and artistic achievements at the time: a peak they would never again reach.

Applying the imperial phase label to other famous bands yields predictable results: the Beach Boys in the mid- ‘60s; Pink Floyd in the ‘70s; Talking Heads in late ‘70s and early ‘80s; R.E.M. in the early to mid ‘90s; and Radiohead from late ‘90s through the late ‘00s. Of course, some bands can escape this label—specifically, those that broke up while still at their creative and commercial zeniths—the obvious examples being the Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, the Police, and the Smiths. But all in all, the imperial phase is something that almost every well-known, long-lasting band experiences—it is, in many ways, inevitable: the result of an eventual decline in artistic momentum.

This article isn’t meant to be about the imperial phase, but I thought it prudent to mention before introducing a band that, in my opinion, represents its antithesis: Talk Talk.

For me, the story of Talk Talk is less about the actual happenings and more about the path taken—the stark juxtaposition between where they began and where they ended. Thus, in this article, I’ll stray from an in-depth analysis of their creative works, leaving that to sources at the end which, in my view, describe them better than I ever could. So, let’s begin…

Synth-pop Darlings

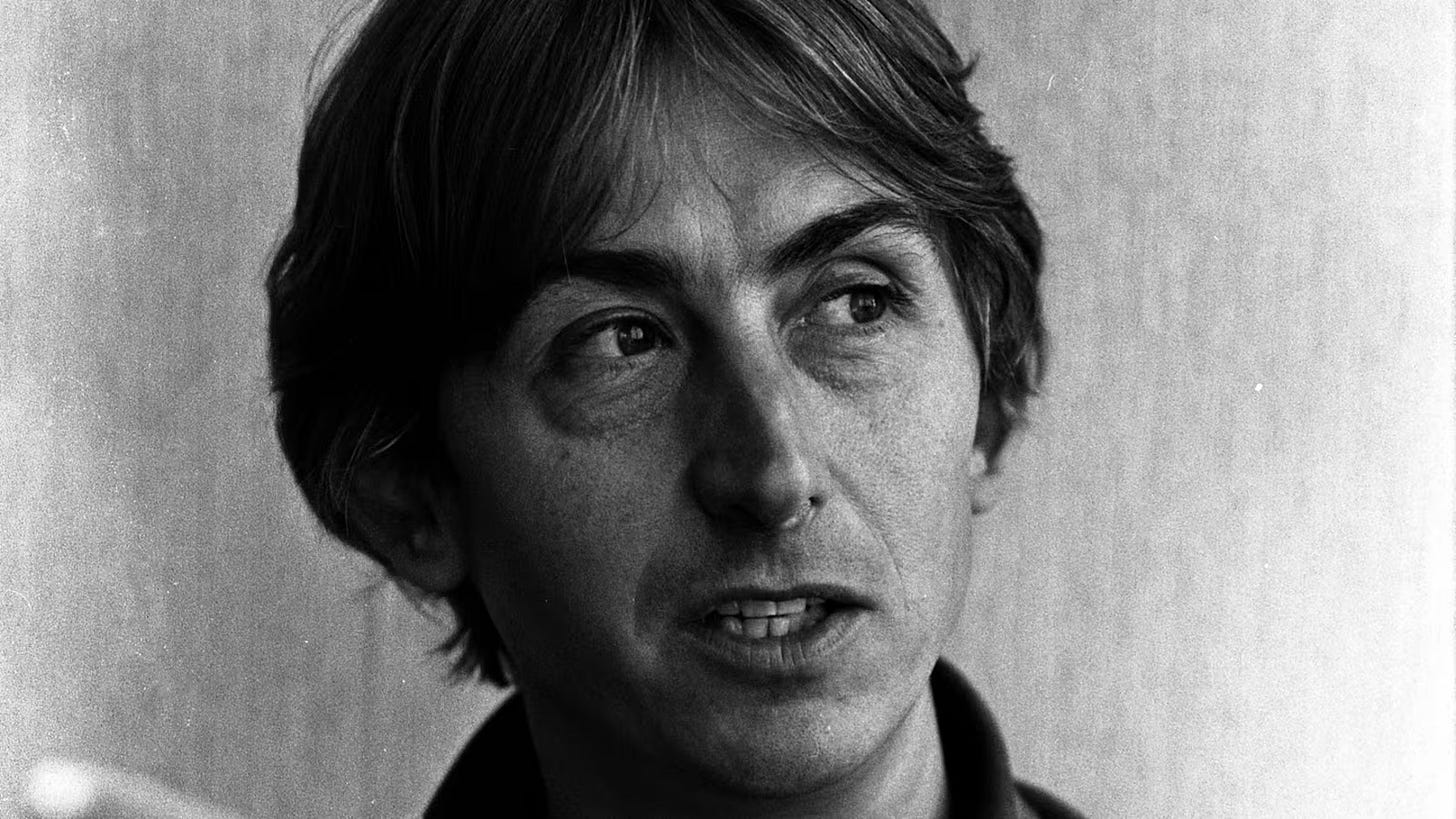

Talk Talk started life in 1981, formed in London by drummer Lee Harris, bassist Paul Webb, keyboardist Simon Brenner, and singer-songwriter Mark Hollis. In their early days, the band embraced the burgeoning New Romantic movement, drawing inspiration from groups like Duran Duran, A Flock of Seagulls, and Spandau Ballet. They released their first album, The Party’s Over, the following year and saw moderate success, with the record peaking at #22 on the UK charts.1 Led by their singles “Mirror Man,” the eponymous “Talk Talk,” and “Today,” the band established themselves as a capable synth-pop act on their very first outing—producing material that, while not extraordinary, was catchy enough for mainstream success and even earned modest praise from critics (see Neil Tennant’s review in Smash Hits below).

Upon revisiting The Party’s Over after listening to the band’s catalogue in its entirety, I found it as good—and perhaps even slightly better—than I remembered. It’s simply a fun listen, with a sound so ubiquitous to the era of its birth, and a lyric superficiality that goes hand in hand. In retrospect, the potential was all there: the outstanding musicianship and Hollis’ matchless vocals pointed towards a bright future for Talk Talk.

From here, Talk Talk’s story could have gone in an entirely different direction. They could’ve taken the easy route and—like so many other bands—fallen into a rut, where creative risk-taking is sacrificed for popular appeal and financial stability: the allure of fame and fortune. Instead, they began a reinvention—gradual at first, but one that would soon accelerate dramatically.

On the Road

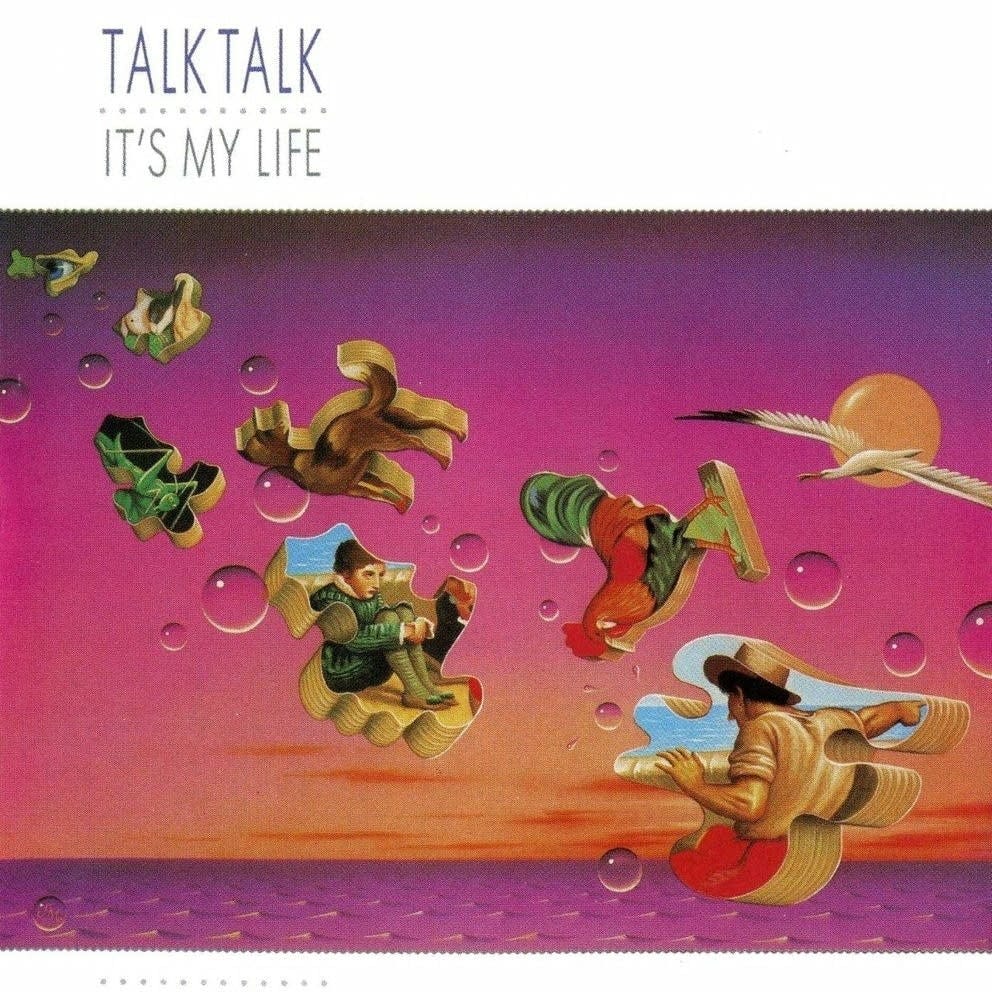

Talk Talk’s second album, It’s My Life, was released in early 1984—with one of the most distinct covers of all time (see below): a Dali-esque interpretation of a John Everett Millais painting, courtesy of James Marsh. Inexplicably, the album charted poorly in the UK, reaching just #35.2 This was an anomaly, most likely due to poor marketing by their label, EMI. Elsewhere in Europe, however, the album performed remarkably well—peaking at #4 in Germany,3 #3 in the Netherlands,4 #2 in Switzerland,5 and even #42 in the US6—the band’s highest chart position stateside to date.

The album was led by the now-iconic eponymous single, “It’s My Life,” which reached #31 on the Billboard Hot 1007 and #1 on the Billboard Dance Club Chart,8 along with its second single, “Such a Shame,” which performed well in continental Europe—reaching #1 in Switzerland.9 While synths are still the dominant force on It’s My Life, a more layered soundscape has begun to emerge—piano, trumpet, and acoustic guitar add warmth and counteract the cold, precise synthesizers. Through this analog shift, Hollis’ jazz inspirations also began to surface—albeit only in the background, for now.

Overall, It’s My Life proved a decisive release for the band, signaling a shift in mindset—though one not fully realized. In an interview with the Dutch magazine Oor, Hollis laments, "There are an awful lot of synthesizers on the second album, that's true. But we use the synthesizer for organic sounds, not synthetic. … We can’t afford an orchestra, but we can use synthesizer in an economically responsible way and move in that direction. In fact, I really hate the instrument.”10 A blunt statement—if slightly disingenuous, given the sheer abundance of the very thing he claims to hate on the record. Nevertheless, the sentiment remains, as does his aspiration to break free.

Stepping Out

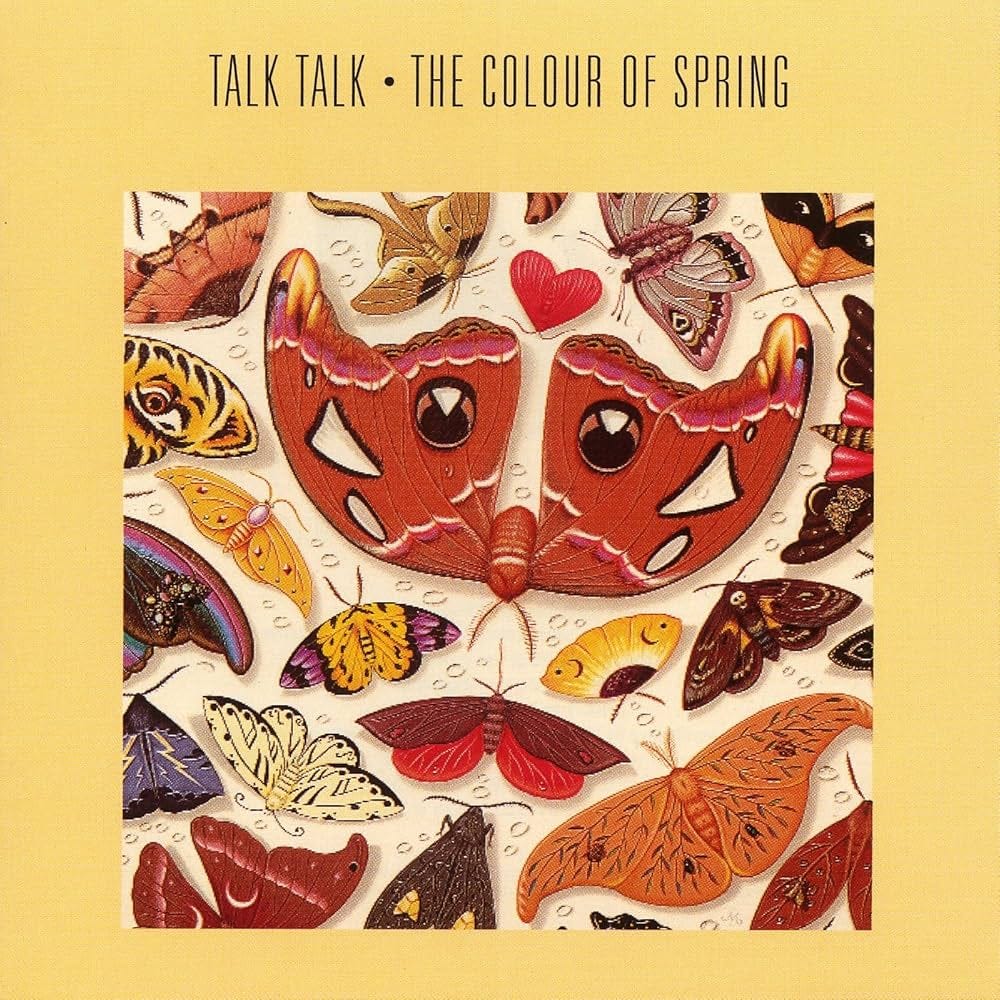

Talk Talk followed up It’s My Life with its most successful studio album: 1986’s The Colour of Spring. Hollis stayed true to his word—the synths were no more—and in their place stood the acoustic instruments that once lingered in the background of the previous record, along with some eclectic new additions: harp, saxophone, and harmonica—and some obscure ones: melodica, mellotron, variophon (look them up), and even a children’s choir— à la “Another Brick in the Wall.” And with that, Hollis finally achieved that “organic sound” he so greatly sought—and in spectacular fashion, too.

Buoyed by the hit singles “Life’s What You Make It,” “Living in Another World,” and “I Don’t Believe in You,” the band found a balance between commercial and artistic success—perhaps even unintentionally; they never worried about promoting their music—just making it—with Hollis even refusing to lip-sync in the “It’s My Life” music video, preferring instead to tape his mouth shut.

Revisiting the idea of an imperial phase, The Colour of Spring should’ve marked this stage for the band. But in many ways, its release became the moment Talk Talk’s artistic and commercial trajectories intersected—one line trending upward, the other trending sharply downward. Abnormal… very abnormal indeed.

The Colour of Spring charted well in the UK—especially compared to the disappointing performance of It’s My Life—reaching #8.11 However, the album did slightly poorer elsewhere, reaching just #58 on the Billboard Hot 200.12 So, while it expanded on the commercial success of its predecessor, it only did so marginally—but creatively, it did so in spades.

Some New Beginnings

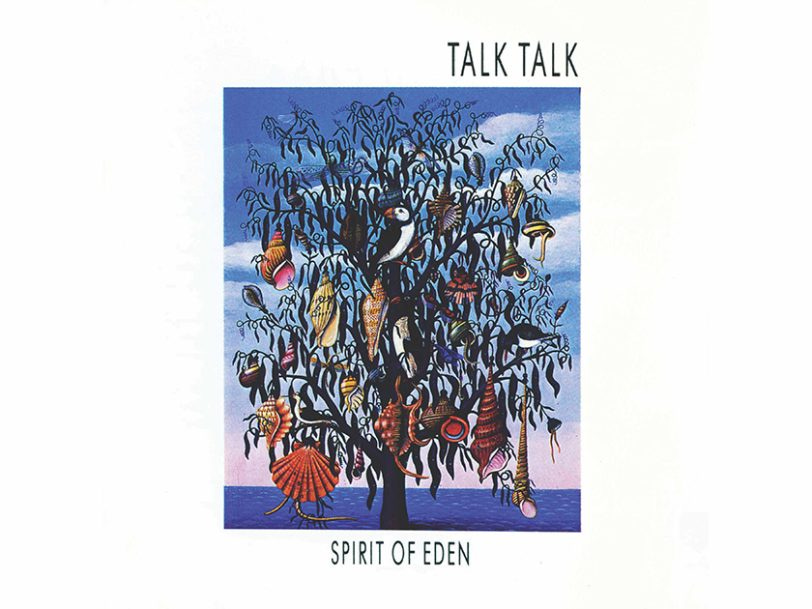

So, back into the studio Talk Talk went. For nearly a year—led by Hollis—the band recorded countless hours of improvised material, often working in near-total darkness. What emerged was strange, to say the least. These weren’t songs in the traditional sense, but rather extended musical compositions, later edited and reassembled into an album. Representing by far the most radical departure of their career—and perhaps any band’s—Talk Talk released their fourth studio album, Spirit of Eden, in late 1988.

Immediately, there are about a thousand notable changes. Hollis’ vocals are now unintelligible—reminiscent of Michael Stipe’s on the early R.E.M. albums—and function more as another instrument: the lyrics irrelevant, pitch, tone, and his matchless delivery, everything. On the first several tracks, high-distortion electric guitar rules the show, oscillating between intense crests and silent troughs, filled in with Hollis’ roaring voice. The later tracks are more peaceful, allowing ambience to flow—anguished vocals leading the way, trailed by a thick tapestry of eclectic instrumentation carried over from The Colour of Spring. Its final track, “Wealth,” patiently dissolves into silence, with the notes of an organ fading for nearly a full minute.

One fascinating phenomenon of a would-be pop album with largely incoherent lyrics is that the tracks tend to blur together, making it a challenge to connect the music to individual songs—or even to recall their names, for that matter. So, when it came time to release a single—something the band had fought vehemently against—the label insisted, and they begrudgingly chose “I Believe in You.” Despite being shortened from 6:15 to 3:40 for radio play, the song—rather unsurprisingly—did not perform well, reaching a disappointing #85 on the UK charts.13 The album itself fared similarly poorly, peaking at #19 and spending just six weeks on the chart14—The Colour of Spring had stayed for 21.

Talk Talk lost many fans with Spirit of Eden, and critics were polarized—largely due to the album’s sheer strangeness. In its review, Q called it “the kind of record which encourages marketing men to commit suicide,”15 nevertheless awarding it four out of five stars. Unfazed, Hollis remarked in an interview with the magazine that he is motivated by the need to make great, increasingly personal music—not money. The commercial suicide would continue.

Commercial Suicide Continued

Talk Talk spent the months following Spirit of Eden’s release locked in a legal battle with their label, EMI, as they fought to break free from their contract. They were ultimately successful, signed with Polydor Records, and began work on their next record. By this point, the original quartet had dwindled to just two members: Hollis and Harris.

Released in September 1991—the same month as Nirvana’s Nevermind—Talk Talk’s fifth album, Laughing Stock, marked the completion of the band’s transformation—from Duran Duran wannabes to industry pariahs. The synth-pop era would end later that year, dethroned by grunge—though Talk Talk wouldn’t care, or probably even notice.

Laughing Stock saw the already minimal compositions from Spirit of Eden stripped to the bone—to the point of abstraction. The tracks no longer felt continuous, as they had on the last record; instead, long bouts of silence—sometimes occurring mid-track—came to dominate. Each instrument now stands alone, as if peaking out into the quiet, and Hollis’ vocals are distant and even less articulate, rendering them almost completely indiscernible.

All of this, as seen before, made for an unmarketable album. Imagine a track that goes still halfway through—like “Taphead”—being played on the radio. It’d never happen. So, despite three singles being released from Laughing Stock—“After the Flood,” “New Grass,” and “Ascension Day”—none of them cracked the UK Top 100. The album itself hardly did better, peaking at #26 and falling off the chart in just two weeks.16 Reviews were, once again, mixed: critics puzzled by the album. It received two out of five stars in Rolling Stone’s Album Guide the following year17 (see review below), which, remarkably, was the highest rating any Talk Talk album received. Ouch.

This proved to be the end of the road for Talk Talk. After the release of Laughing Stock, the band quietly disbanded—Hollis citing his desire to focus on his family. But this is not the end of the story.

Leave in Silence

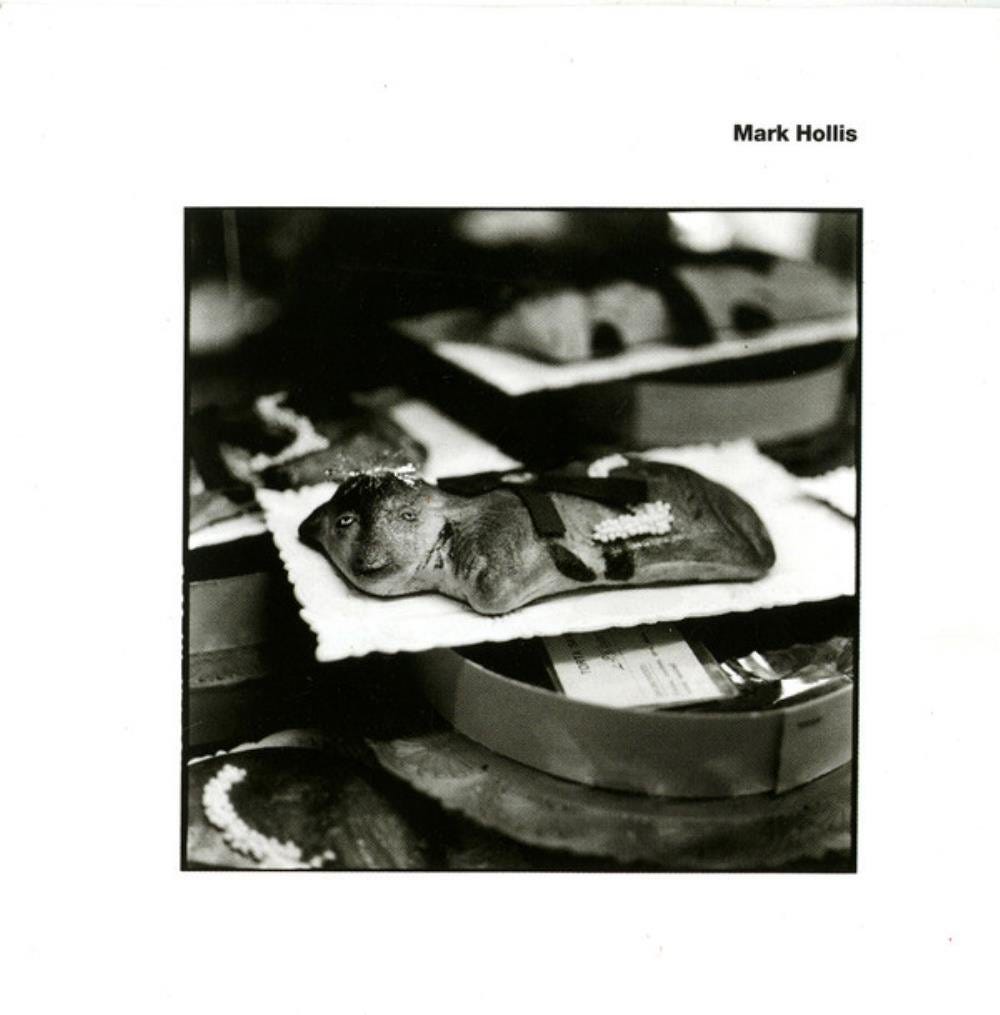

After more than half a decade away from the music industry, Mark Hollis returned in 1997 and began work on what was intended to be the sixth Talk Talk studio album, titled Mountains of the Moon, thus fulfilling the band’s two-record contract with Polydor. But ultimately—perhaps owing to Hollis’ near-total control over the production process—the album was released as a solo project under his own name in early 1998.

This album is somber—and, as has been the case for nearly two decades, it moves even further from the band’s synth-pop roots. The tracks are almost entirely acoustic, the vocals clearer, and the structure more linear than on either of Talk Talk’s last two albums. These aren’t experimental compositions, but rather quiet meditations—resigned in tone. The whole record feels like one long ending: the listener waits for it, is teased by it—and finally after 47 minutes and eight tracks, it arrives.

To state the obvious, Mark Hollis was not a hit. The album reached just #53 on UK chart before dropping off entirely the following week.18 No singles were released, and Hollis didn’t perform live, saying, “There won't be any gig, not even at home in the living room.”19 And as tone of his compositions hinted, this would be his final album. Talk Talk made a flashy entrance in 1982—but in 1998, Hollis left in silence.

A Second Glance

Mark Hollis passed away from cancer on February 25th, 2019, at the age of 64—six years ago today. Two decades removed from the music industry, he left this world with nothing left to prove—to himself or anyone else. If you listen to his eponymous album—the only solo effort of his career—it sounds like a valediction. As the music fades away, just like its composer, you’re left to reflect. And in my opinion, never has so much been done with so little.

Talk Talk has received renewed attention since their disbandment over three decades ago. Their most commercially unsuccessful works—Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock—are now regarded as not only their best, but as some of the greatest albums of all time. The band is often credited with almost singlehandedly shaping an entirely new musical genre: post-rock.

On the community-driven website RateYourMusic, Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock receive ratings of 4.08 and 4.13 out of 5, respectively, and are ranked as the second- and fifth-greatest albums of 1988 and 1991.20 And in 2013, NME ranked Spirit of Eden the 95th best album of all time.21 Remarkably, each of Talk Talk’s albums is rated higher than the one before it (see below)—an almost unheard-of feat.

Truth be told, prior to stumbling upon this website, I had only known Talk Talk for their first two albums—and mostly for two of their singles: “Talk Talk” and “It’s My Life.” So I was bewildered, to say the least, when I finally saw this table. Why did these synth-brats have not just one, but two of the highest-rated albums of all time? So, I decided to give the band’s last three albums a listen—and… they’re all good. Very good. I’ve relistened to them—Laughing Stock in particular—many times since.

A Final Word

Something must be addressed about Talk Talk—and their fans: there’s an undeniable air of pretentiousness in how both the band’s music and career are viewed. Case in point: the band’s first two albums—The Party’s Over and It’s My Life—are objectively strong synth-pop records—records that actually contain songs, not extended jam sessions—yet they receive barely any love. Granted, the band’s later works are undeniably more innovative and nuanced, but that doesn’t make what came before poor in quality—just because it was mainstream. Alas, Hollis himself—if he were still alive—would probably disagree with this.

Mark Hollis was many things: a visionary, a minimalist, an ardent non-conformist—but he was also something of a snob, often viewing the work of other artists—especially those in synth-pop—as innately inferior to his own, as if unaware of where his own career began. He also had a habit of name-dropping his influences in interviews: Satie, Bartók, Debussy, and the like—and in that same Q interview referenced earlier, he even grew combative when the interviewer remarked that Spirit of Eden makes for great background music (which it does), saying: “You should never listen to music as background music. Ever.”22 Thanks for the advice, Mark.

This pretentiousness is disappointing—slightly diminishing the mystique of the band’s career—but it doesn’t need to be fueled. One benefit of starting out as a band that made good music—and only improved from there—is that there’s no right or wrong place to begin listening. Talk Talk made great music from beginning to end—and really, it was only the audience that came and left, then returned, after the party was already over.

There’s something noble about sticking to your principles through thick and thin—abandoning wealth and the life of pop stars to focus on what truly mattered: family and, of course, making great music. Incredibly unique, high-quality music that never got the respect it deserved. Most bands make music for others. Talk Talk? They made music for themselves.

Notable Reviews:

The Party’s Over Review:

"One sad mood permeates the whole LP as though they're compensating for the fact that they'd like to say something important but can't think of anything to say. Still, attractive tunes and synthesizer phrases plus sliding bass-playing prosper in the big, careful production. If only they'd cheered up, the part[y] might have been much more enjoyable."

- Neil Tennant, Smash Hits23

Spirit of Eden Review:

“Talk Talk’s fourth LP is the kind of record which encourages marketing men to commit suicide. Mark Hollis’s outfit are nicely poised for major success this time around after spending the best part of a decade gradually building up a ground swell of support for their quirky, sophisticated pop. 1986’s The Colour Of Spring had the obligatory hit single in the shape of Life’s What You Make It and contrived to go gold on Britain while expanding their substantial European following. But two years later Mark Hollis has designed a record whose six songs flow into one another like one long mood piece without a hint of a single and with a peculiarly old world feel to the subdued orchestral mutterings that accompany his faltering high-pitched musings.

“Spirit Of Eden strives for a totality of mood in the manner of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, or Neil Young’s On The Beach. Like the Young LP, these six songs are largely downbeat and drowned in introspection. Fragments of keyboard lines or sudden bursts from a guitar or an oboe break through the contemplative calm that suffuses Hollis’s brave new world while his vocals barely pick out the lyrics, occasional phrases drifting into earshot like the delayed echo of a cricket ball against bat somewhere in the hazy distance.

“Apparently these songs touch on everything from paradise to heroin addiction yet all remain within the record’s overall mood of calm won from the storm. If Spirit Of Eden often recalls the pastoral epics of the early 70’s, it has a range, ambition and self-sufficiency that enables Hollis and co to step out of time and into their own. No hit singles then but a brave record that is not afraid to follow its own muse and damn the consequences.”

- Mark Cooper, Q24

Talk Talk Catalogue Review:

“Good bands usually improve over time, while bad bands generally just fall apart. But Talk Talk took a different approach with its musical growth; instead of getting better or worse, this band simply grew more pretentious with each passing year. On “Talk Talk,” from the Talk Talk EP (which was absorbed into The Party’s Over), the group sounds like an artier Duran Duran, while It’s My Life finds it bumbling along like an ersatz Japan, all exotic color and tremulous vocal mannerisms. Finally, by Spirit of Eden, Mark Hollis’s Pete Townshend-on-Dramamine vocals have been pushed aside by the band’s pointless noodling.”

- J.D. Considine, Rolling Stone25

Album Analyses

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/talk-talk-the-partys-over/

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/talk-talk-its-my-life/

https://www.offiziellecharts.de/charts/album-details-141

https://dutchcharts.nl/showitem.asp?interpret=Talk+Talk&titel=It%27s+My+Life&cat=a

https://hitparade.ch/album/Talk-Talk/It's-My-Life-141

https://www.billboard.com/artist/talk-talk/chart-history/tlp/

https://www.billboard.com/charts/hot-100/1984-05-19/

https://www.billboard.com/charts/dance-club-play-songs/1984-05-05/#

http://swisscharts.com/song/Talk-Talk/Such-a-Shame-1133

http://www.snowinberlin.com/itsmylife.html

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/talk-talk-the-colour-of-spring/

https://www.billboard.com/artist/talk-talk/chart-history/tlp/

https://www.officialcharts.com/songs/talk-talk-i-believe-in-you/

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/talk-talk-spirit-of-eden/

http://www.snowinberlin.com/spiritofeden.html#q-1988-10-00a

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/talk-talk-laughing-stock/

https://archive.org/details/rollingstonealbu0000unse/page/691/mode/1up?view=theater

https://www.officialcharts.com/albums/mark-hollis-mark-hollis/

https://web.archive.org/web/20091009000251/http://www.palyniam.co.uk/content.php?page=interview-mark

https://rateyourmusic.com/artist/talk-talk#google_vignette

https://www.nme.com/photos/the-500-greatest-albums-of-all-time-100-1-1426116

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/aug/28/from-rocks-backpages-talk-talk

https://www.flickr.com/photos/51106326@N00/7375702858/in/album-72157630135930028

http://www.snowinberlin.com/spiritofeden.html#q-1988-10-00a

https://archive.org/details/rollingstonealbu0000unse/page/691/mode/1up?view=theater