Zen Arcade: A Journey Through Noise

Dissecting the early career of Hüsker Dü and story behind their legendary 1984 double album.

Abrasive for abrasive’s sake? As with their neighbors The Replacements, one can’t help but wonder whether Hüsker Dü might have been something more than just a hidden gem of the 1980s alternative scene—perhaps the Midwest’s answer to R.E.M.

Yes, Hüsker Dü: the hardcore band from Minnesota—who put out six studio records, a live album, and an EP between their formation in 1979 and breakup in 1987. How could they possibly be compared to R.E.M., the archetypal American indie band?

Well, it’s all a matter of the music… Abrasiveness killed The Replacements’ career—just not through their music. A perpetual string of drunken shenanigans did The ‘Mats in, even earning them a lifetime ban from SNL (watch it here).

Hüsker Dü took a different route to ensure they’d never see mainstream success: by making their music as unfriendly to listeners as possible.

A Minneapolis Sound

When discussing American cities and their associated music scenes, a few iconic ones stand out—like San Francisco’s psychedelic movement, New York’s punk scene, and Seattle’s grunge proliferation. Another, from two cities not typically viewed as cultural powerhouses, took shape in the early 1980s and helped mold nearly every form of alternative and grunge rock that followed: Minneapolis hardcore.

The word “hardcore” is somewhat charged, conjuring images of rowdy teenage boys—with just a little too much time on their hands—sporting tattoos and mohawks. And while that’s not entirely off the mark, it’s a slightly misleading way to describe the sound that emerged from Minneapolis and St. Paul.

The Minnesotan flavor of hardcore strayed from the fast, aggressive, anarchic sound embraced by bands like Black Flag and Bad Brains—it was more personal and emotional, while retaining that intensity. The Minneapolis sound was something of a reversed Trojan horse: intimidating on the surface, vulnerable at its core.

The two groups that best encapsulated this dichotomy were the aforementioned Hüsker Dü and The Replacements. And while these kindred bands are both incredible and have yet to receive their due for reshaping indie music, this article will focus solely on Hüsker Dü’s contributions to rock history—I’ll get to the ‘Mats eventually, I promise.

Zen Arcade

Hüsker Dü is a lot like the meek, cowardly lion: scary on the surface, soft on the inside. “Obnoxious,” “shrill,” “senseless”—these are words often thrown at their music, especially their early work. In spite of these critiques, their hearts proved strong—and their songwriting, remarkably versatile. This is especially true of their second studio album, widely regarded as their magnum opus: Zen Arcade.

Zen Arcade is a total oddity of a record—at the time of its release, and at any time before or since. First and foremost, it’s incredibly long: a double album clocking in at just over 70 minutes. In that time, listeners are greeted with 23 eclectic tracks whose instrumentation resists classification—it’s a record without a label. Despite this variation, there is continuity across these disparate songs—an elaborate narrative. Zen Arcade is a concept album.

The band suffered from a dynamic that while making violent, abrupt breakup an inevitability, also fueled a storied songwriting rivalry between its two lead singers—one clearly apparent on this record. So, before continuing with our exploration of Zen Arcade, let’s introduce this trio.

The Fastest Band in the World

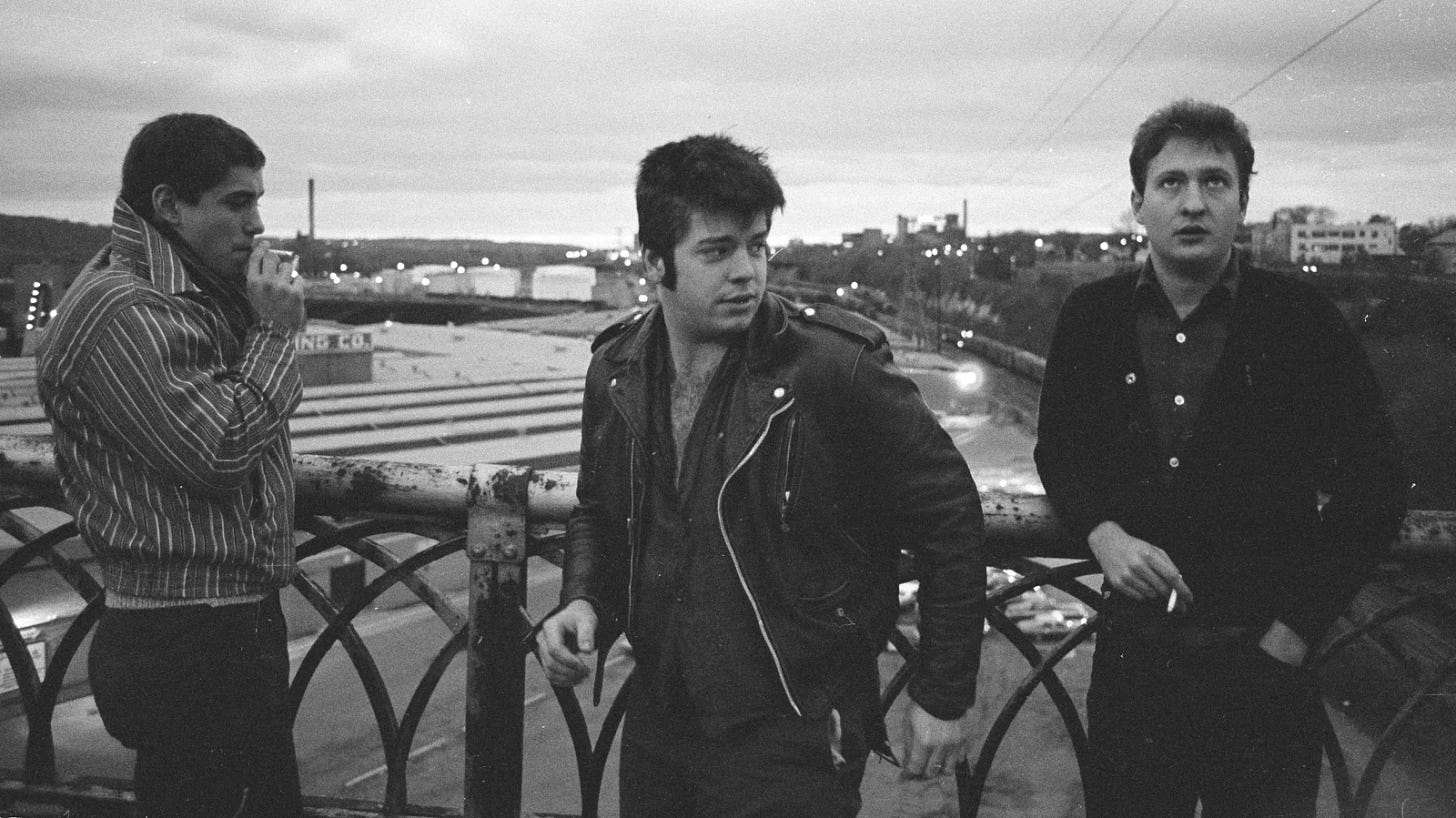

Hüsker Dü was formed in 1979—not in Minneapolis, but in St. Paul, Minnesota—by guitarist Bob Mould, drummer Grant Hart, and bassist Greg Norton. The three met at a record store—as seems to be a trend with rock bands—and bonded over their similar tastes in music, deciding to form a band.

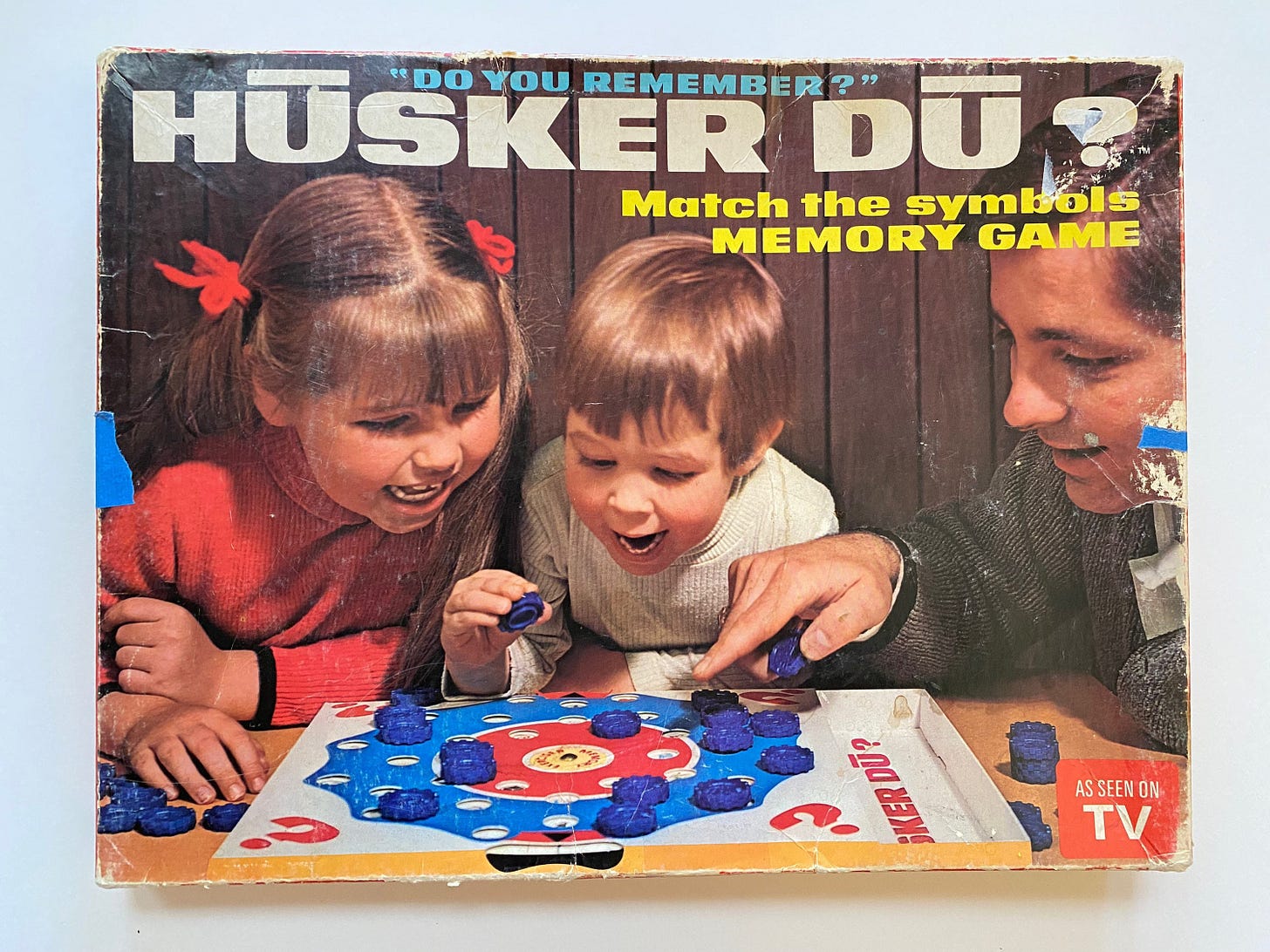

The band took their name taken from a 1950s memory board game— translating from Norwegian to “do you remember?”—though they swapped the macrons (¯) for heavy metal umlauts (¨).1

In the beginning, the trio mostly stuck to playing cover songs—by punk bands like the Ramones—but quickly tried their hands at writing original material. Now, these originals were songs in their loosest form—more aptly, they were exercises to test the limits of how fast they could possibly play their instruments. And they took these compositions on the road.

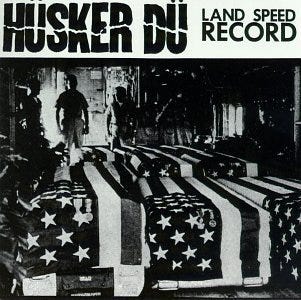

Hüsker Dü’s first “album,” Land Speed Record, was recorded at a show at Minneapolis’ 7th Street Entry on August 15th, 1981. It was done on a 300-dollar budget—it sounds like it cost even less—primarily to showcase the songs they’d touring with—and includes about 26-minutes of material.

Even though this record is, quite honestly, a barrage of noise that renders the individual tracks nearly indecipherable, it served a valuable purpose: showing off their intensity. By this point, the band was faster and tighter than almost any in the hardcore scene—or any other, for that matter. They were seasoned musicians and burgeoning songwriters—if only they’d turned down the amps enough to prove it…

Everything Falls Apart

A sizeable shift emerged for Hüsker Dü on their next two releases: 1983’s Everything Falls Apart and the Metal Circus EP. The former—a mini studio album, just 19 minutes long—was largely a continuation of the Minnesota hardcore pioneered on Land Speed Record. However, as it was not recorded live, the production quality is significantly improved, though—as is a trend we’ll soon see—it’s still quite poor for a studio album.

Another trend: the songs are slightly toned down in intensity and more melodic, giving them, at long last, individuality. Bob Mould took the helm as chief songwriter on this record—though he still shared vocal duties with Grant Hart. And although the lyrics remain inarticulate, a more emotionally varied band has materialized—not just the pure, raging energy of Land Speed Record, but something a little more methodical and restrained.

But despite this commendable progress, it’s still more convenient to lump Everything Falls Apart in with Land Speed Record—rounding out their full-hardcore days—than with what would come later that year: Metal Circus.

The Metal Circus EP

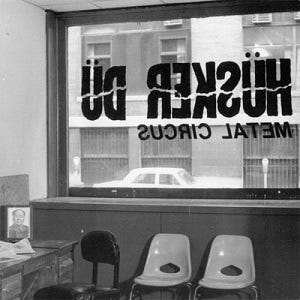

Metal Circus is the first Hüsker Dü record that I’ll listen to for fun. Everything that came before is just too loud and distorted—too much a product of its era and scene to translate well into the present day. Of course, it’s probably because I don’t particularly care for hardcore music that Land Speed Record and Everything Falls Apart just didn’t click—and I wasn’t the only one who thought so.

Metal Circus—released in October 1983—was a turning point in Hüsker Dü’s discography, convincing listeners outside the hardcore scene to finally pay attention to the band. It was their first release where songs exhibit considerable melodic variation—almost in conflict at times. Yet the trademark intensity remains, spearheaded by Mould on tracks like “Real World” and the surprisingly catchy “First of the Last Calls.”

Hart finally emerges as an accomplished songwriter on this EP, contributing two of the seven tracks: “It’s Not Funny Anymore”—before The Smiths, I might add—and his breakthrough: “Diane.” Written about the murder of a West St. Paul waitress by serial killer Joseph Ture Jr., the song is emotionally raw and instrumentally reserved—letting Hart’s anguished voice carry the track. “Diane” is the first classic Dü song, and it proved that a hardcore band didn’t have to be devoid of feelings—other than anger.

For these reasons, Metal Circus was given the R.E.M. treatment: generous college radio airplay—placing Hüsker Dü at the forefront of the medium that birthed the college rock movement. Today, the terms “college rock,” “alternative rock,” and “indie rock” are often used interchangeably.

Though “college rock” as a genre has largely fallen out of fashion, it speaks to where alternative and indie music proliferated: on college radio. Hüsker Dü were now reaching listeners beyond the hardcore sphere—into the flourishing alternative music scene. The stage was now set for what would follow…

And They Did It in One Take

Now, with this background out of the way, Hüsker Dü began work on what would be their second—and really, first full-length—studio album, Zen Arcade, in the summer of 1983. They jammed for hours on end in a vacant St. Paul church, building a repertoire of new song ideas, which they took to the recording studio that October.

An interesting note: for the majority of their career, Hüsker Dü’s label, SST Records, waited upwards of six months between the recording, mixing, and release of the band’s records. So, just as the trio entered the studio to make Zen Arcade, Metal Circus was being released. The positive reception of their more melodic, emotional sound had no impact on the decisions made for Zen Arcade—though it no doubt would have emboldened them further.

Zen Arcade was recorded at Total Access studios in Redondo Beach, California. Remarkably, according to the liner notes, of the album’s 23 tracks, all but the opener—“Something I Learned Today”—and “Newest Industry” were recorded in a single take.2 The entire recording and mixing process took just 85 hours and cost a mere $3,200. Hüsker Dü had their masterpiece finished before year’s end, though it wouldn’t see the light of day for many more months.

Hardcore Darlings

On July 3rd, 1984, Zen Arcade was released with an initial production run of between 3,500 and 5,000 copies, which promptly sold out.3 Unlike other pioneering albums that are often misunderstood in their own time, only to be reexamined years later—à la The Velvet Underground & Nico—Zen Arcade was overwhelmingly well received upon its release by fans and critics alike.

David Fricke of Rolling Stone called the record “probably the closest hardcore will ever get to an opera.”4 And Zen Arcade placed #8 on The Village Voice’s Pazz & Jop poll for 1984—a compilation of music critics’ top ten albums of the year—amusingly enough, behind two other Twin Cities releases: The Replacements’ Let it Be and Prince’s Purple Rain.5

However, Zen Arcade—like any hardcore or hardcore-adjacent record—was born under a bad sign: inaccessibility. General audiences and mainstream radio were unwelcoming to Hüsker Dü, which meant that, even as it found favor in enclaves like college radio, it remained fated for only small-scale success.

So, after the initial pressing of approximately 5,000 copies sold out—and the months-long wait for more to be made, which certainly hurt its momentum and sales—Zen Arcade went on to sell 20,000 units by spring 1985.6 Unimpressive by mainstream rock’s standards, but admirable by indie’s—and undeniably a strong return on a $3,200 investment.

Members at War

A notable change from Hüsker Dü’s earlier work was the introduction of individual songwriter credits on Zen Arcade—at Mould’s request. This marked an early sign of the rivalry taking shape between Grant Hart and Bob Mould: a formidable battle between two accomplished musicians, vocalists, and songwriters.

Glancing at the 23 tracks—each of which we will examine in greater detail shortly—the final tally stands at twelve songs by Mould, five by Hart, and six credited to more than one band member. While this may suggest Mould carried the bulk of the workload on Zen Arcade, it’s important to distinguish quantity from quality.

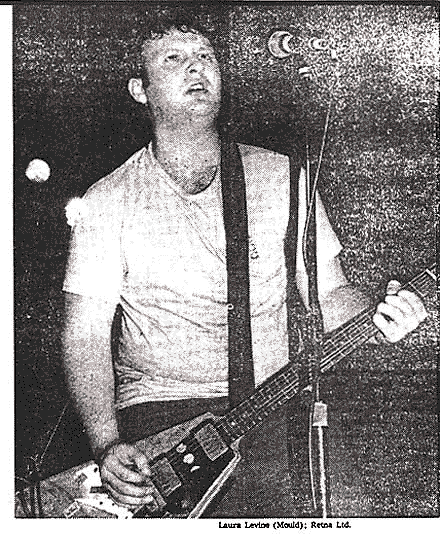

Grant Hart’s five tracks on Zen Arcade are among the very best on the record. A September 1984 New York Times review of the album—accompanied by a lone photo of Mould—offered this assessment:

“The band's guitarist, Bob Mould, is turning into an exceptionally gifted songwriter; the three most immediately impressive songs on ‘Zen Arcade’ (‘Turn On The News,’ ‘Standing By The Sea,’ and ‘Pink Turns To Blue’) would be superb material on any band's album.”7

It’s worth noting that all three of these tracks were written by Hart—not Mould—making this what must have been an incredibly frustrating read for the unacknowledged songwriter.

Hart and Mould carried their feud across each of Hüsker Dü’s subsequent releases, with Hart eventually earning near-equal writing credits—four to Mould’s five on Candy Apple Grey (1986), and nine to Mould’s ten on their swansong, Warehouse: Songs and Stories (1987). Hart later claimed there was “a ‘dictum’ determined by Mould prohibiting [him] from ever writing more than 50% of the material on any release.”8

Songs and Stories

At this point, we’ll examine the 23 tracks on Zen Arcade in detail and trace the continuity that defines it as a concept album. In all honesty, the story is difficult to discern from the songs themselves, largely because of Mould’s prominently distorted guitar, which often drowns out the vocals on most tracks.

Zen Arcade is hardly consistent in most respects, including the quality of its tracks. They vary from vocal-less interludes less than a minute long to a closer that stretches nearly 14 minutes. For this reason, the analysis devoted to some songs may be significantly longer than to others.

Something I Learned Today

Zen Arcade begins with a bang. If there were ever a perfect fusion of hardcore intensity and pop’s emotional resonance, it might be “Something I Learned Today.” This track captures Mould at his strongest: his painfully strained vocals deliver a burst of rage, his guitar thunders without overpowering the other elements. Norton contributes a memorable bass lick, and Hart, a militaristic beat.

The story opens with the protagonist’s realization of the world’s rules: “Black and white is always gray,” “Yield to the right-of-way,” and “Never look straight in the sun's rays,”—“Someone else's rules, not mine.” It’s not the most obvious interpretation, but the track’s fast pace and Mould’s repeated refrain, “Something I Learned Today,” in the outro set the tone: a youth’s disillusionment with authority—all packed into under two minutes.

Broken Home, Broken Heart

This song’s meaning is more on the nose: the struggle of growing up in a broken home. The protagonist endures his parents constantly fighting, not “know[ing] who’s wrong or right,” and crying himself to sleep every night.

Another Mould track, “Broken Home, Broken Heart” continues the tone set by the previous—this time with an extended guitar solo. You might expect it to end forcefully, with a blast of noise, but instead, it uncharacteristically fades slowly into the void. A good song, but not a great one.

Never Talking to You Again

Hart’s first contribution to the record, “Never Talking To You Again” is the ultimate minimalist track—just 100 seconds long and featuring a single instrument: a folksy acoustic guitar. Not exactly the go-to choice for a hardcore band.

Sandwiched between two of Mould’s zealous offerings, the song’s placement enhances its soberness: our protagonist is severing his ties to his family—or possibly a romantic figure—and making his own way in the world. Regardless, “Never Talking To You Again” is certainly a happy surprise for any first-time listener. Who knew the Hüskers even owned an acoustic instrument?

Chartered Trips

In my opinion, Mould’s best track on Zen Arcade, “Chartered Trips” has an the infectious beat and catchiness of a pop-hit—while retaining the focus and passion that makes Hüsker Dü’s music so special.

Similar in many ways sonically to the album’s first two entries, this track serves as the careful culmination of the first act of the story. The protagonist has finally left his home for good: “said ‘there’s no returning, from this chartered trip away.’”

“Chartered Trips” is one of several songs on the album that make me wonder what a mainstream hit it could’ve have been if the distortion were only turned down—I guess we’ll never know.

Dreams Reoccurring

Four tracks into Zen Arcade, and we’ve already encountered hardcore, folk-rock, and a hardcore-pop hybrid. Now, on the fifth track, we’re introduced to yet another possibly made-up genre: hardcore-psychedelic.

“Dreams Reoccurring” is an instrumental track, so its meaning is more theoretical than most—just an educated guess, really. It features a prominently hypnotic guitar sound, achieved by Mould layering feedback and loops, complemented by Hart’s snare roll.

Though psychedelic in nature, the sound doesn’t suggest someone at peace—more likely, it reflects the agitated, disturbed psyche of our protagonist after he’s run away from home. It’s a brief, intriguing experiment in sound—brief for now.

Indecision Time

One of the few entries on this record I could do without, “Indecision Time” is probably the track most reminiscent of the Land Speed Record days. It has a cool guitar solo toward the end, but otherwise it’s Mould screaming at the top of his lungs for two minutes.

However, though not a pleasant listen, this song does effectively illustrate the uncertainties and insecurities of our protagonist: “Back and forth between the good and the bad / It’s indecision time.”

Hare Krsna

Our second psychedelic track, “Hare Krsna,” is an intriguingly bizarre mashup of Hindu spiritual practices—complete with mantra-like chanting—and a ‘50s Bo Diddley beat reminiscent of the 1965 classic, “I Want Candy.”

Similar to “Dreams Reoccuring,” Mould employs a feedback loop—this time incredibly high-pitched, evoking the violent ringing of bells. The effect is creepy and cult-like, signaling that the protagonist has turned to religious fanaticism as a way to feel accepted in the world.

It may not be the easiest track on the ears, but it’s certainly one of the most imaginative ones.

Beyond the Threshold

“Beyond the Threshold—may not be joyful listening—as is becoming a trend on the record—but it perfectly illustrates the next chapter in the story: the protagonist unraveling as life away from home proves no sanctuary.

Hart’s manic drumming and Mould’s hurried, muttered vocals are a perfect match, paired—of course—with the Dü’s signature heavy, distorted guitar.

Mould goes from whispering, “Greetings from home / I wish you were here / Hear what I say / But you can't hear me at all,” to ending the song by screaming its title repeatedly. Needless to say, it seems like our protagonist is having a tough go of it…

Pride

Musically, “Pride” is really just a continuation of the previous track, “Beyond the Threshold,” though narratively it does serve a purpose—perhaps explaining its inclusion on Zen Arcade.

The protagonist continues his descent into lunacy, but—as I interpret it—refuses to return home or ask his family for help because of his pride, even as he longs to confide in someone. It’s a track we could all probably do without.

I’ll Never Forget You

The last of a string of three very similar songs, “I’ll Never Forget You” is, thankfully, the best of the trio. It kicks off with a rare audible bassline from Norton, then continues at haste with a jumpy guitar riff and Mould repeatedly screaming the song’s title.

While the title may suggest a song about coping with loss, this track instead captures the protagonist severing ties with those he once tried to confide in—people who refused to accept him. In retrospect, Mould’s screams of “I’ll never forget you” sound less like expressions of love, and more like threats.

The Biggest Lie

An exceptionally restrained entry, “The Biggest Lie” is a breath of fresh air after a string of intensely aggressive tracks. It opens with a slow buildup—forty seconds of a two-minute song—leading into Mould’s vocals, which encapsulate the protagonist’s newly bitter worldview: it’s all the biggest lie.

What’s Going On

We’ve reached the halfway point of Zen Arcade—by track count, if not by runtime—and “What’s Going On” marks a turning point of the record.

First off, I have to note that Norton’s opening bassline sounds strikingly similar to the intro of Smashing Pumpkins’ “1979”—an iconic riff from a song released eleven years later. The resemblance is uncanny—though I’ll give Billy Corgan and company the benefit of the doubt.

For the first time in eight tracks, we get a contribution from Hart—his second on the record. “What’s Going On” is yet another example of a song that, in a perfect world, would have been a pop-radio hit. Its lyrics are catchy, its guitar incredibly melodic, and the background piano—banging like something out of a Little Richard tune—is a lovely touch.

After the fury of almost ten Mould tracks, our protagonist finds himself at peace, admitting: “I was talking when I should have been listening / I didn’t hear a word that anyone said.” He’s gained some self awareness, however, he remains confused, even delusional; Hart’s repeated refrain “What’s going on inside my head”—becomes a haunting echo. This is melodic hardcore and Hüsker Dü at their very best.

Masochism World

“Masochism World” is probably the first—and only—hardcore song with a church choir singing backup, but there should be more, because surprisingly, it works. Otherwise, it’s a slightly inhibited track, featuring Hart lead vocals. A fun, creative listen—certainly in the upper half of Zen Arcade tracks.

Here, our protagonist takes a turn for the worse, exploring his masochistic tendencies with conflicting results: “I love it, I hate it, I love it, I hate it too.” He is dangerously unhinged and well along on a path of self- and collateral destruction.

Standing by the Sea

“Standing By The Sea” opens with ambient noise and an ominous bassline from Norton, setting a unique, intriguing tone. Another track written and sung by Hart, it likely earns the distinction of having the fewest guitar parts on the record—and stands as one of the most atmosphere-driven, too. We can only assume Mould was quite bored during this song’s recording.

This track is also pretty self-explanatory: the protagonist stands alone by the ocean, contemplating his circumstances and decisions.

Somewhere

Another bubble-gum pop song disguised as hardcore, “Somewhere” is Hart’s third lead vocal in a row—he undeniably dominates the second half of Zen Arcade. This track is typical of the band’s melodic hardcore, with hints of psychedelia, courtesy of Mould’s layering and feedback.

Our protagonist continues to feel disillusioned: “Searching for the truth but all I ever find is lies.” But somewhere, he imagines finding “happiness instead of pain,” though this statement doesn’t feel especially promising.

One Step at a Time

This forty-second interlude seamlessly fades in from the previous track, “Somewhere,” feeling more like a continuation than a standalone piece. Still, credit where it’s due: “One Step At A Time” is strikingly ethereal, making expressive use of piano and, once again, overturning every preconceived notion about hardcore bands.

“One Step At A Time” serves as a buffer in the protagonist’s story—the calm before the storm, so to speak.

Pink Turns to Blue

A song as good as “Pink Turns to Blue”—far and away the strongest on the record, and one of the greatest ever—is tragic in many ways. The guitar is so distorted and forceful it drowns out Hart’s incredible lyrics. Its harsh production all but guaranteed it would never be a hit, even though everything’s there—sonically and lyrically.

But that’s its genius: it doesn’t need to sound beautiful to be beautiful. Written and sung by Hart, the track tells the story of the protagonist’s girlfriend, who spirals into addiction and dies of an overdose. Hart utters the high-pitched refrain, “I don’t know what to do / Now that pink has turned to blue,” over and over—it stays with you.

Newest Industry

After string of incredible Hart songs, Mould is back in the driver’s seat on “Newest Industry”—an incredibly cynical song with a pertinent political message. It opens with an R.E.M.-esque guitar riff and toes a fine line, balancing passion with restraint—it has just the right amount of each.

This track is lyrically absurd, describing a post-apocalyptic world with the opening line: “We been through mass destruction once but once was not enough,” before going on to talk about annexing Mexico, living in caves, and corporate overlords.

It’s not completely clear how this fits into the story—the protagonist might be delusional again, or perhaps he genuinely believes a world so cruel to him is indeed heading in this direction. Either way, it’s a refreshing track that ushers Mould back into the spotlight.

Monday Will Never Be The Same

Yet another piano-driven instrumental under a minute in length, “Monday Will Never Be The Same” is, in my opinion, the best of the bunch. At this point, though, there’s not much more to say—good work, Hüsker Dü.

Whatever

“Whatever” acts as a resolution to “Broken Home, Broken Heart”—some eighteen tracks ago. Back when the protagonist lived at home, he felt neglected and abused by his parents. Now, after enduring immense pain while living alone in the world, he’s had an epiphany.

He’s realized the plans he made aren’t possible: “He finally gets the nerve one day, now life becomes a test.” Mould repeats “Mom and dad, I’m sorry,” followed by the protagonist’s new mantra: “Whatever you want, whatever you do, wherever you go, whatever you say.”

It’s not a happy resolution, but a resolution nonetheless.

The Tooth Fairy And The Princess

At this point, things get really weird—we’re thrown right back into psychedelic hardcore. Featuring Mould’s feedback loops—which now sound reminiscent of the Beatles’ Revolver or Sgt. Pepper’s—the track feels extremely sparse and ambient, with no drums or bass.

Instead, Mould’s echoing voice repeats the lines: “Don't give up,

don't let go, don't give in, don't let on,” which are subsequently echoed by Hart and Norton. Then, he whispers the key line: “In your bed, late at night, red hot red, don't get up,” followed by a scream and the end of the song.

It was all a dream…

Turn On the News

You might expect the previous track, “Tooth Fairy and the Princess”—which dismantles the carefuly constructed narrative of the past twenty-one songs—to serve as the finale. But no—Hüsker Dü follows that cop-out bombshell with one of the record’s finest: “Turn on The News.”

Hart’s final track begins with the distorted sounds of radio broadcasts, then erupts into a fiery song about media saturation and emotional alienation. Though we’ve stepped outside the protagonist’s story, “Turn on the News” still carries the torch. Mould adds an electrifying guitar solo, and just like that—another phenomenal track.

Reoccurring Dreams

The other instrumental tracks on Zen Arcade are brief—all under one hundred seconds in length. But to close the album—in true Hüsker Dü fashion—we’re greeted by a monstrosity of song: fourteen minutes long.

“Reoccuring Dreams” is essentially an extended version of its sister track, “Dreams Reoccuring,” and to those who choose to listen to it in its entirely—all the power to you. Personally, I like to bow out once this track begins.

A Final Note

We’ve done it—we’ve reached the end of Zen Arcade. As you may have picked up on, it can be an especially daunting listen the first time through, and incredibly hard to vividly capture its singular, enigmatic qualities in writing.

If you’re brave of heart and curious to experience one of the oddest—yet most enduring and influential—albums of its era, bring an open mind and give Zen Arcade a listen.

https://americansongwriter.com/behind-the-band-name-husker-du/

https://www.metrotimes.com/music/this-guy-took-the-time-to-remaster-husker-dus-watershed-1984-punk-album-zen-arcade-2300819

Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981-1991 by Michael Azerrad (PDF page 202)

https://web.archive.org/web/20071001003552/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/huskerdu/albums/album/110848/review/5944241/zen_arcade

https://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/pnj/pjres84.php

http://www.mmmm.eclipse.co.uk/press/HuskerDu-MM5-85.htm#:~:text=The%20strangest%20side%20effect%20of,on%20a%20Next%20Big%20Thing.

http://www.thirdav.com/zinestuff/nyt0984.html

https://www.spin.com/2017/09/grant-hart-husker-du-breakup-interview/